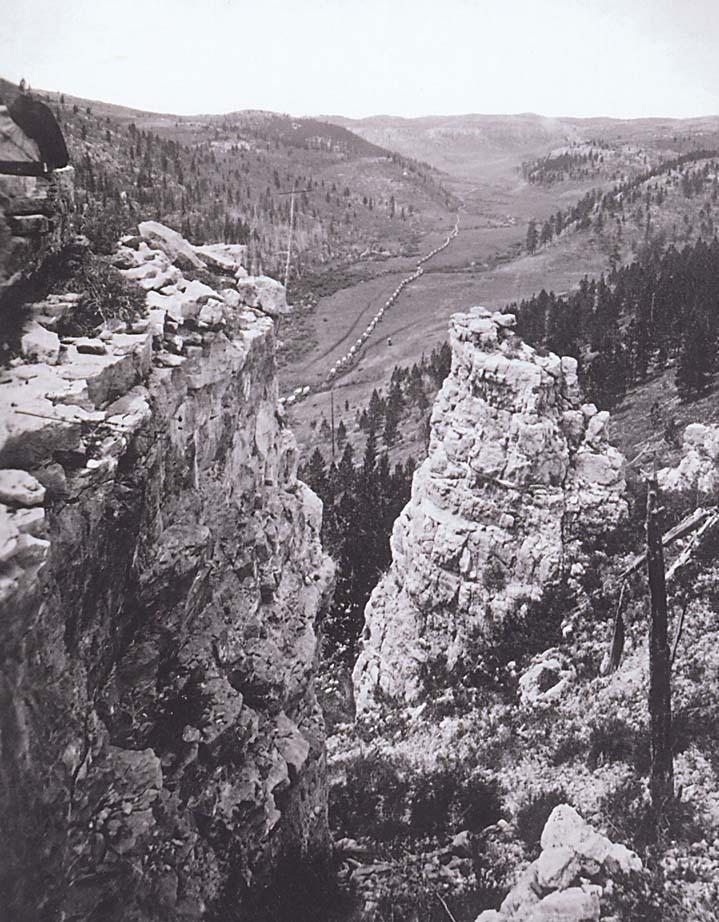

1874 Black Hills Expedition photograph by W.H. Illingworth

1874 Black Hills Expedition

Background

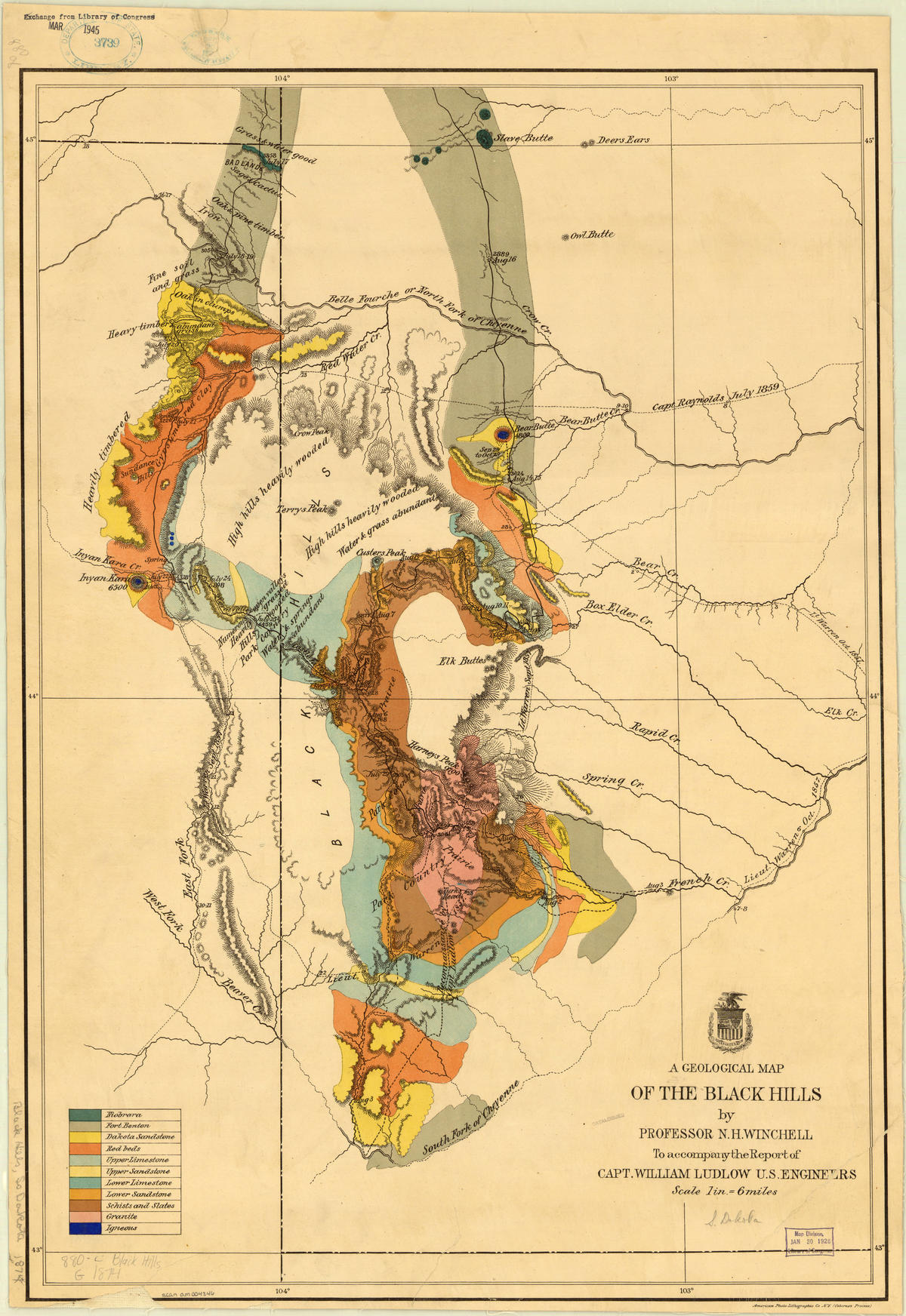

In the summer of 1874, less than two years after he came to Minnesota, our department’s founder, Newton H. Winchell, joined Custer’s Black Hill Expedition as part of its four-person scientific corps. The other members of the corps were George Bird Grinnell, who later became a noted naturalist, his assistant Luther North, and A. B. Donaldson, another ‘Minnesota State University’ professor who was Winchell’s assistant geologist and botanist

Hired by the military, this scientific corps was a legitimate part of the expedition under the terms of the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie. However, in violation of that treaty, Custer also allowed four journalists and two civilian miners (Horatio N. Ross and William T. McKay) to accompany the expedition.

The official purpose of the 1874 Black Hills Expedition was to find a site for an outpost that could curtail Lakota raids on Cheyenne reservations and among the military’s higher levels that may have been the expedition’s true goal. The Lakota nation was a powerful military force, and many U.S. military leaders did not wish to provoke open warfare with a dangerous foe. However, among western Euro-American communities, the expedition’s ‘real’ purpose was to prove that gold was present in abundance in the Black Hills. The United States was struggling through the economic panic of 1873, and if gold was discovered, that discovery could pave the way for the Black Hills to be taken from the Lakota. That the Lakota were aware of the expedition’s potential consequences is reflected in the name they gave the expedition’s wagon wheel rutted trail - the ‘Thieves Road’.

Gold 'Discovery'

It is often reported that the expedition was the first to discover gold in the Black Hills, but at the time nearly everyone in the region knew that gold was present in the hills, as a few Lakota had previously traded gold for goods. Moreover, traces of gold are present in nearly every western mountain range and stream, as attested to by thousands of shallow shafts dug by miners futilely trying to track traces of 'color' or thin promising seams. Hence the question at the time was not whether there was gold in the Black Hills, but whether it was present in economic quantities. Answering that was the miner's goal and it is unlikely they succeeded.

The 1874 Expedition moved quickly through the Black Hills, so quickly that Winchell was dismayed at how little time he had for reconnaissance. Although the civilian miners panned for gold throughout the trip, it was not until the expedition reached the plains east of present-day Custer that they claimed they found gold. However, the extent of gold found remains highly questionable as this ‘gold discovery’ did not significantly impact camp life beyond enticing a few men to temporarily join the miners’ search.

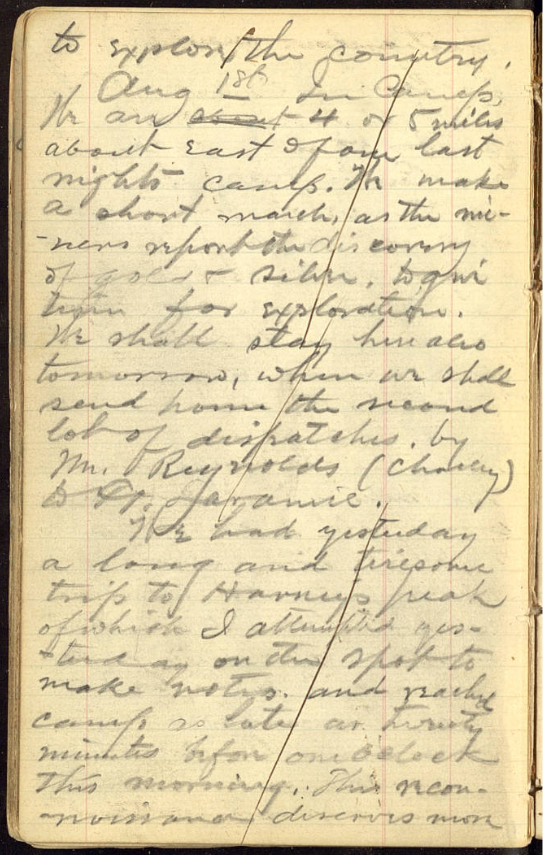

In his journal entry for August 1, Winchell noted the expedition only made a short march of 4 to 5 miles since the last camp as the miners reported discovering gold and silver, so they were given time for exploration. He later said he had not seen gold himself and doubted its quantity. Custer would disparage Winchell for those statements, claiming in western newspapers that the only reason Winchell had not found gold was that he hadn’t looked for it. However, Lt. Colonel Fredrick Grant, the expedition’s second in command and President Grant’s son, supported Winchell. In Grant’s official expedition report, he wrote that the miners ‘showed the same pieces every day’, an amount he estimated as roughly two dollars’ value. He concluded that ‘I don’t believe that any gold was found at all.’

Fred Power, a temporary correspondent for the Saint Paul Daily Press, became a companion of the two miners (Ross and McKay). In his diary entry of July 31, amid a vivid description of the valley’s beauty, wildflowers, and streams, Power noted that gold had been discovered in quantities, also silver. His diary does not mention any gold finds on August 1st and 2nd, despite others’ later claims that the most significant finds were made on those days. Most of his August 1st entry was devoted to describing a champagne party the command officers had while Custer and Winchell were away climbing Harney Peak. Power’s August 3rd entry reported that ‘We remained quietly in camp, Fishing, prospecting, & amusing generally, as best we could. Ross got some good specimens of gold & McKay, silver qua[r}tz.’ Yet, whatever, Ross and McKay found that day did not seem to make much of an impact. His next day entry began ‘Every thing continued in the same old way. Col Tilford being in comd of camp’. McKay chose to go out hunting with Power rather than following up his prospecting. A few days later, Power noted that on August 8th, ‘McKay found gold just after leaving our camp.’ Despite his personal relationship with McKay, Power’s dispatches lacked the sensationalism of other journalists. In his dispatch of August 2, he simply wrote ‘Oh! I forgot to say gold has been discovered’ but made no claims of it being in significant amounts.

Although gold would eventually be discovered in commercial quantities in the Black Hills, those rich deposits lay in the northern part of the range around Deadwood and Lead, areas never visited by the expedition.

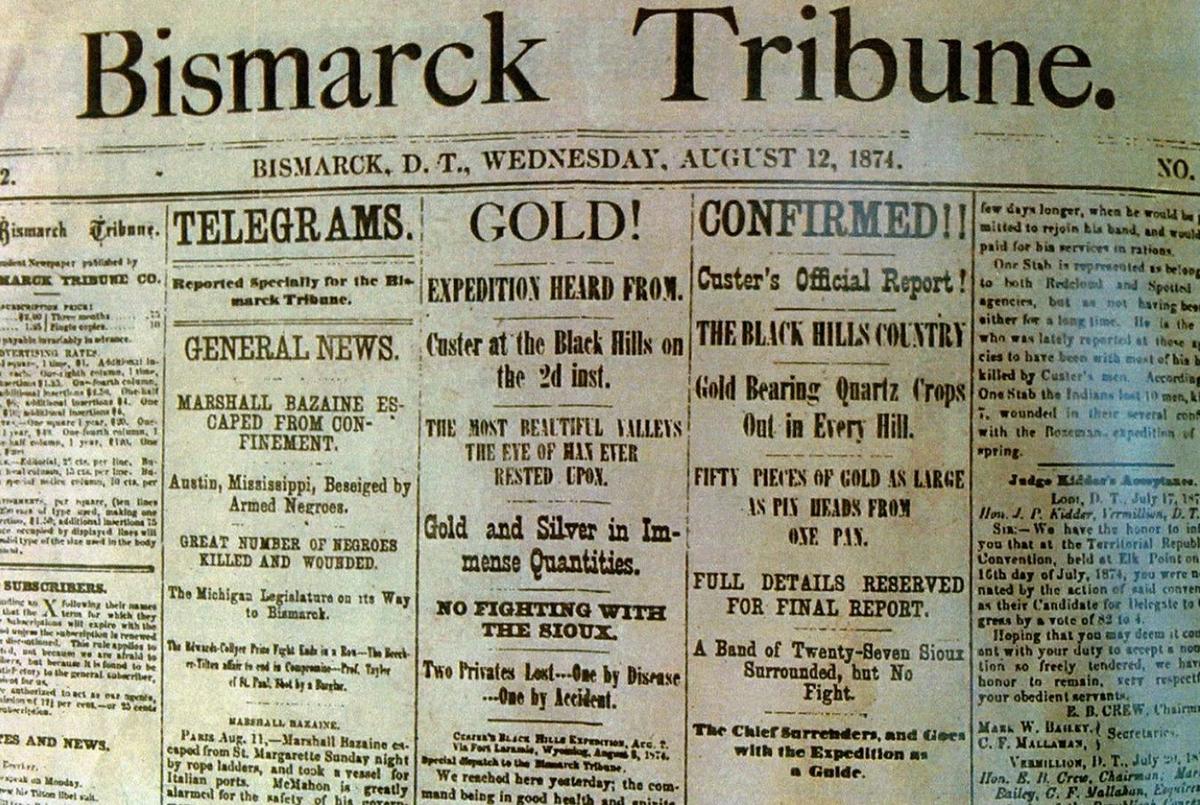

Yet Custer allowed the accompanying journalists to report there was gold ‘from the grass roots down’ and later boasted of the gold’s abundance. However, in his official reports he was careful to be more guarded, only noting that miners had reported gold in possibly commercial quantities. Custer did say that he had in front of him ‘forty or fifty small particles of pure gold, in size averaging that of a small pin-head and most of it obtained today from one pan-full of Earth’ and he went on to state that the miners had reported finding gold among the grassroots. However, he never confirmed he saw gold in place nor that he had seen it taken. Knowing full well the public’s intense interest in gold, it seems inconceivable Custer would not take the time to personally verify the presence of gold if it had been abundant.

Even more condemning was the expedition members’ remarkable lack of response to this gold ‘discovery’. Although the miners and a group of teamsters, including the expedition’s only female member (Sarah Campbell - a cook who had had won her freedom from slavery in a lawsuit at the age of 12), organized themselves into a corporation to make a claim if the land should open for settlement, whatever was found on the banks of French Creek in August of 1874 was not enough to entice a single member of Custer’s expedition to leave. Even the civilian miners returned with the expedition rather than stay to work finds they would later claim were rich enough to yield $150 a day. In contrast, when gold was discovered in California, so many soldiers left to prospect for gold that the Army had to grant furloughs to avoid wholesale desertions.

Custer’s command consisted of 1000 soldiers, along with hundreds of teamsters and civilian cooks, yet no one left the expedition after the supposed gold discovery. The few soldier diaries from the expedition either neglect to mention gold or dismiss it as some ‘excitement’ in camp that day. However, the lackadaisical reaction of the expedition members was not reflected by the frenzied response to the published reports of gold in western newspapers. Those wildly inflated reports touched off a gold rush craze and calls to seize the Black Hills, a land theft that would cause tragic, irreparable harm to the Lakota people and lead to many deaths two years later at the Battle of Pezi Sla (Little Bighorn) and far more in the following years.

A century and a half later, it is impossible to know with certainty what transpired during the opening days of August 1874. Perhaps the best evidence that the miners did find traces of gold (rather than 'salting' the outcrops as some later contended) is that Ross returned to the area and spent the remainder of his life prospecting around what became the city of Custer. However, in thirty years of searching, Ross never found any riches. In a poignant reflection of the probable meagerness of the original finds, Ross primarily supported himself by charging tourists and greenhorn miners to see the location of his 1874 'discovery'.

Aftermath

At one point, even Custer seemed to realize the consequences of his decisions. In an uncharacteristically reflective letter sent to the New York Times, Custer wrote:

“We are goading the Indians to madness by invading their hallowed grounds and throwing open to them a terrible revenge whose cost would far outweigh any scientific or political benefit possible to be extracted from such an expedition.”

The scientific benefit Custer mentioned, were the samples and information collected by the expedition’s Scientific Corps. Today, the record of this historic expedition is largely documents: government reports, newspaper stories, a few journals, and some 70 photographic images captured by William H. Illingworth. Winchell’s rock and mineral samples comprise some of the few physical relics of an expedition that sparked momentous changes across the Great Plains and had incalculable costs to the Lakota people.

For many decades, it was assumed that Winchell’s Black Hills samples had been lost, but recently roughly half of the rock and mineral samples were found disseminated and often mislabeled in our departments’ scattered collections. Use the link below to see images of Winchell’s rock and mineral samples.

Winchell's Black Hills Rock and Mineral Samples

1874 Black Hills Expedition members photographed by W.H. Illingworth on August 13. NessiRAhpat (Bloody Knife), Arikara scout and Newton H. Winchell (wearing hat and with hands clasped behind his back) stand in front of tent opening. George Custer lies on ground in center.

Winchell identification by Ernest Grafe and Paul Horsted in 'Exploring with Custer - The 1874 Black Hills Expedition a great resource for anyone interested in following the details of the 1874 expedition.