‘Indigenous’ is highlighted by quotation marks here because these early studies were not truly Indigenous as they did not include Indigenous perspectives, knowledge, or experiences. Instead, they were archaeological investigations by one culture of another, by the dispossessors of those they were trying to dispossess.

Although most Dakota had been driven from Minnesota before Winchell arrived, Winchell hired Ojibwe guides for many northern Minnesota geological investigations. Yet his archaeological work was based almost exclusively on his own excavations and the work of non-Indigenous scholars. While this approach severely compromised the validity of his archaeological studies, Winchell was not alone in this regard. The same was true of most researchers at that time. However, this widespread perspective was not based solely on ignorance. Relegating ‘Indigenous’ studies to the past was another way in which Euro-American culture dismissed or ignored contemporary Indigenous communities.

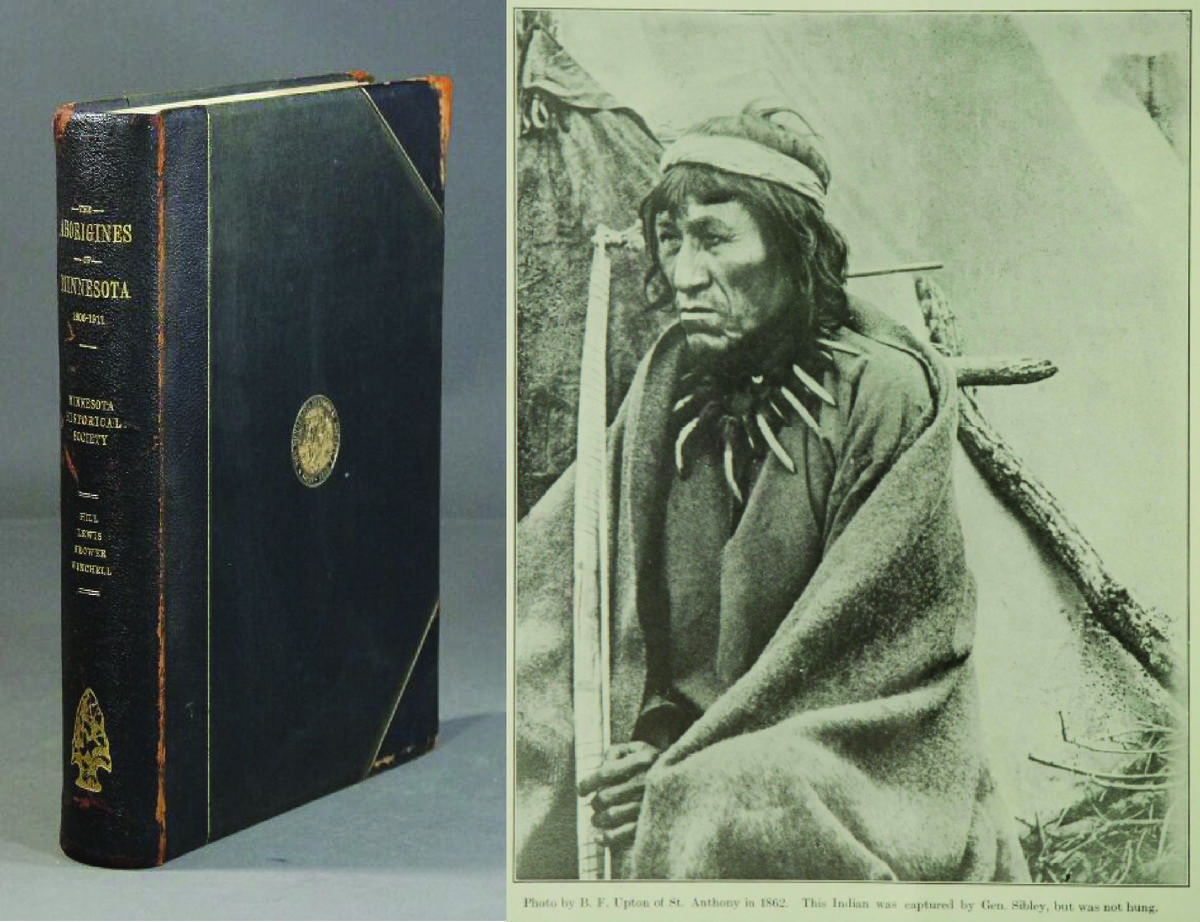

Aborigines of Minnesota and its frontispiece image

‘The Aborigines of Minnesota'

Although none of the 'archaeological' materials mentioned in the previous section still remain in our collection, I have yet to find records of their fate, to know if they were lost, given away, or simply decayed. The museum’s archaeological materials may have been transferred to another department or to the Minnesota Historical Society. After Winchell retired from the Survey, he worked with the Minnesota Historical Society from 1906 to 1911 to complete, edit, and publish the work of Jacob Vandenberg Brower who died in 1905. Winchell’s efforts culminated in his 1911 publication, ‘The Aborigines of Minnesota; a report based on the collections of Jacob V. Brower, and on the field surveys and notes of Alfred J. Hill and Theodore H. Lewis, collated, augmented, and described by N.H. Winchell.’ The volume’s 761 pages and 704 illustrations and foldouts are still referenced by historians and archaeologists. However, Winchell’s work definitely reflected the prejudices of his time. Its frontispiece illustration is a photograph of a Dakota man taken at the 1862 internment camp. Although the photographer, B.F. Upton of St. Anthony, is named, the caption does not acknowledge the Dakota man as an individual, only stating ‘This Indian was captured by Gen. Sibley, but was not hung.’ It is possible Winchell consolidated some of our museum’s archaeological materials with those of the Minnesota Historical Society, but I have not had time to determine whether that occurred.

Some people have argued that Winchell’s collection of skeletal remains and funerary goods was normal for archaeological investigations of the time, and it is true that the practice was widespread and not limited to Indigenous burials. Euro-Americans did much the same with ancient European burials. However, that reasoning fails to consider the deeply racist underpinnings of 19th century archaeological activities. Many Indigenous cultures do not recognize any difference between modern and ancient burials, as all are ancestors. Hence, excavations of burial mounds evoked the same passionate repugnance that Winchell and other 19th century Euro-Americans felt for the ‘resurrectionists’ of their time who stole bodies for medical dissection. The fact that 19th century Euro-American scientists did not consider the Dakota perspective reflects the lower value they placed on Indigenous culture compared to their own. Moreover, paleontologists and archaeologists did not confine their grave robbery to ancient burials. This period was the intellectual highwater mark of the brain size studies that attempted to use brain size as a ‘scientific justification’ for racism (and sexism). A news account of Othniel Marsh’s 1870 Yale expedition included the following passage describing the expedition coming on a scaffold burial.[1]

On one of these tombs lay two bodies -- a woman, decked in beads and bracelets, and a scaleless brave, with war-paint still on the parchment cheeks, and holding in his crumbling hands a rusty shotgun and a pack of cards. Beneath the platform lay the skeleton of the favorite pony, whose spirit had accompanied his master's to the new resting place. A feeling of awe was creeping over us as we built in thought historic castles for the dead, when the professor brought us down to the stern realities of science by the unromantic remark: "Well, boys, perhaps they died of smallpox; but we can't study the origin of the Indian race unless we have those skulls!"

If oral traditions within our department are accurate, at least one early Minnesota paleontologist engaged in the same reprehensible behavior with the remains staying in the department until 1997.

[1] Betts, C.W. "Searching for Dinosaur and Other Prehistoric Animal Fossils." Harper's New Monthly Magazine. 43 (257): 663-671, October 1871.

Winchell at excavation of a Dakota village site in Cambria, MN as seen in 1905(?) postcard image. To the best of my knowledge this excavation did not involve any burials but was solely an investigation of a general village site. (photography courtesy of Blue Earth County Historical Society)

Mound Builders and Dispossession

Further, the background for Winchell’s investigations had deeply troubling roots, even though Winchell tried to indirectly refute some of those racist beliefs. In the 19th century, the myth of a mound builder civilization had taken hold in American scientific circles and was being used to justify racist policies. Despite early French and Spanish explorers encountering Indigenous mound-building cultures and literally viewing mound construction, by the early 19th century there was a widespread belief that the thousands of mounds and mound complexes distributed across the continent were evidence of an earlier mound builder civilization. One that had been violently overthrown and destroyed by the now-extant Indigenous peoples. To the believers of this mound builder cult, the current Indigenous people were savages, incapable of the sophistication the mounds implied. And the cult of this mound builder civilization caused serious repercussions for Indigenous societies.

Although the mound builders’ supposed identity was variously attributed as being a lost tribe of Israel, early Vikings, or, as suggested by Ignatius Donnelly (Minnesota Lieutenant Governor and three term Congressional Representative), the survivors of Atlantis – nearly all the proposed identities were of European origin. Hence the mound builders were supposedly an earlier European civilization that had been destroyed by the continent’s contemporary Indigenous peoples. Consequently, to those who believed the mound builder myth, the Indigenous people of North America were not the continents’ original occupants, but usurpers who had violently dispossessed an earlier European civilization that had first settled the land.

Despite the absurdity of this mound builder myth, its believers were not fringe members of society, but included many individuals with considerable power. President Andrew Jackson, in his first annual message to Congress in 1829 said that:

‘In the monuments and fortresses of an unknown people, spread over the extensive regions of the West, we behold the memorials of a once powerful race, which was exterminated or has disappeared to make room for the existing savage tribes.’

He went on to claim that because of this, the current loss of Indigenous people, while tragic, was inevitable and part of a natural order. After all, these ‘savage tribes’ had themselves stolen the land from others, ones his audience would recognize as having been ancient Europeans. Hence, Indigenous dispossession in Jackson’s view was justified. A few months later, Jackson put his belief into practice, signing the Indian Removal Act into law on May 28, 1830. A half century later, Winchell was attempting to disprove lingering beliefs in a European mound builder civilization by demonstrating the ancestors of the current Indigenous built the mounds across Minnesota. Yet he presented his work in scientific terms, not addressing the underlying racist basis upon which the mound builder cult was built. Nor did he recognize that his own archaeological activities were anathema to Indigenous cultures.

For many Indigenous people, the excavation of burial mounds is the ultimate act of dispossession. In 1914, the same year Winchell died, Frank Drew and others protested the removal of an Ojibwe cemetery on Wisconsin Point near the Fond du Lac Reservation.

“The white men have stolen the Indian land from them. Now, not satisfied, they would tear up the bodies of the Indian dead in order that they may have even the last resting place of our ancestors.”

Frank Drew, Superior, Wisconsin, 1914

Despite their protests, nearly 200 graves at Wisconsin Point were removed and reburied in mass graves near Superior. Not until the summer of 2022 were some land and burials finally returned to the Fond du Lac band’s control. Hence, the theft of remains and funerary goods for display in the General Museum was part of a much larger, often violent, dispossession of Indigenous lands.

Early in his university career, Winchell played a more direct role in the dispossession of Indigenous land when he became part of the Scientific Corps of the 1874 Black Hills Expedition led by George Custer.