Trail Blazer – Field Geologist – Paleontologist – Scientific Librarian

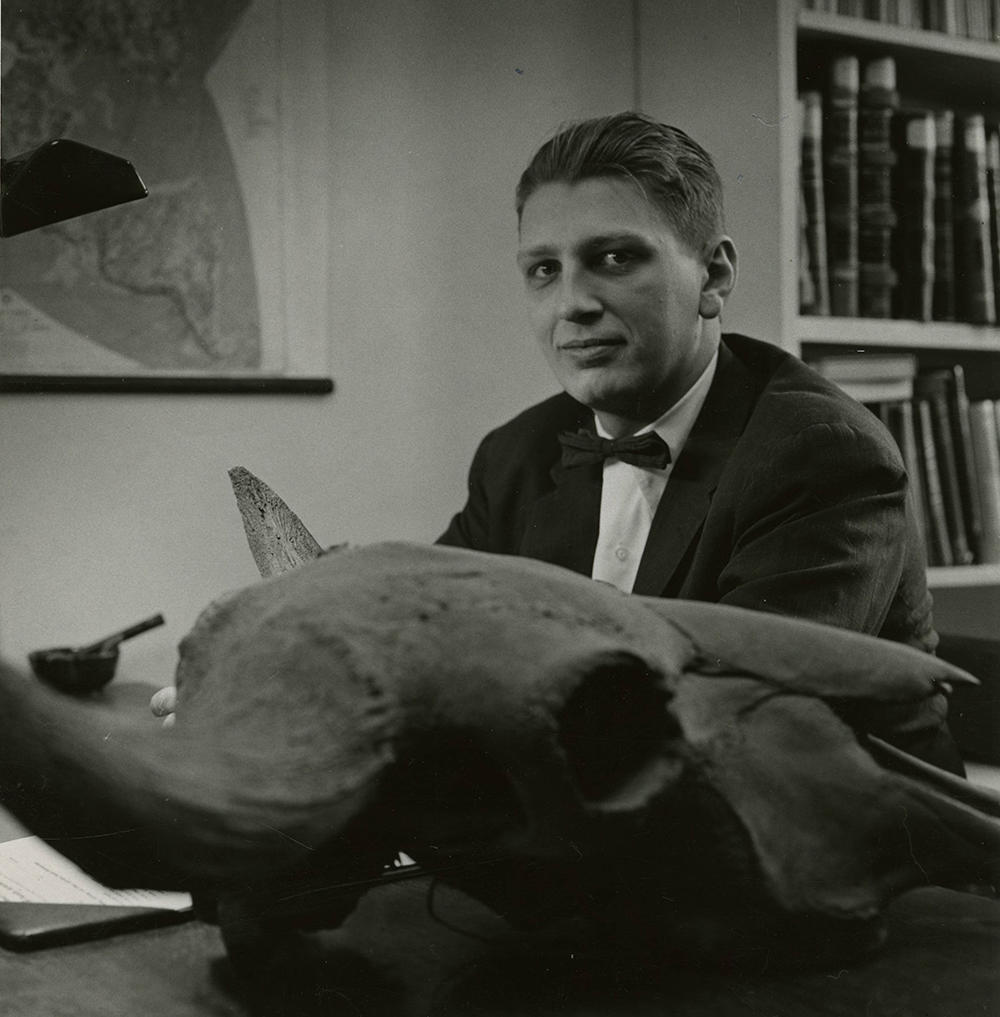

At the age of 27, Eunice Peterson became the first woman to earn a Ph.D. from our department. Like other trail blazers, Eunice had to overcome substantial obstacles to achieve that goal. Yet, a career in geology had not been her original plan, but rather a path she followed almost by chance.

Before the ‘U’

Peterson’s parents were Carl Bernard Peterson and Mattie Emiline Barney. Carl was born to Danish parents at Liberty Pole, WI, a tiny cluster of farms at the intersection of two rural roads in western Wisconsin. Mattie was born on the opposite side of the state in Hayton, but her family moved to Viroqua, Wisconsin, where the two met and in February of 1899 married. Eunice arrived fourteen months later at 8 am on April 6, 1900.

When Eunice was born, Carl and Mattie were living with Mattie’s parents, Frank and Arvilla Barney, sharing the home with Mattie’s sister, brother, and grandmother. Frank was a dentist and although Carl was a schoolteacher, he began learning dentistry under Frank’s guidance. By 1905, Carl, Mattie, and Eunice had relocated to Cashton, WI, a small farming community where Carl served as the local dentist. Three more children followed, but with three years seniority Eunice took on so much responsibility for her siblings that, within the extended family, the four were usually referred to as ‘Eunice and the children.’

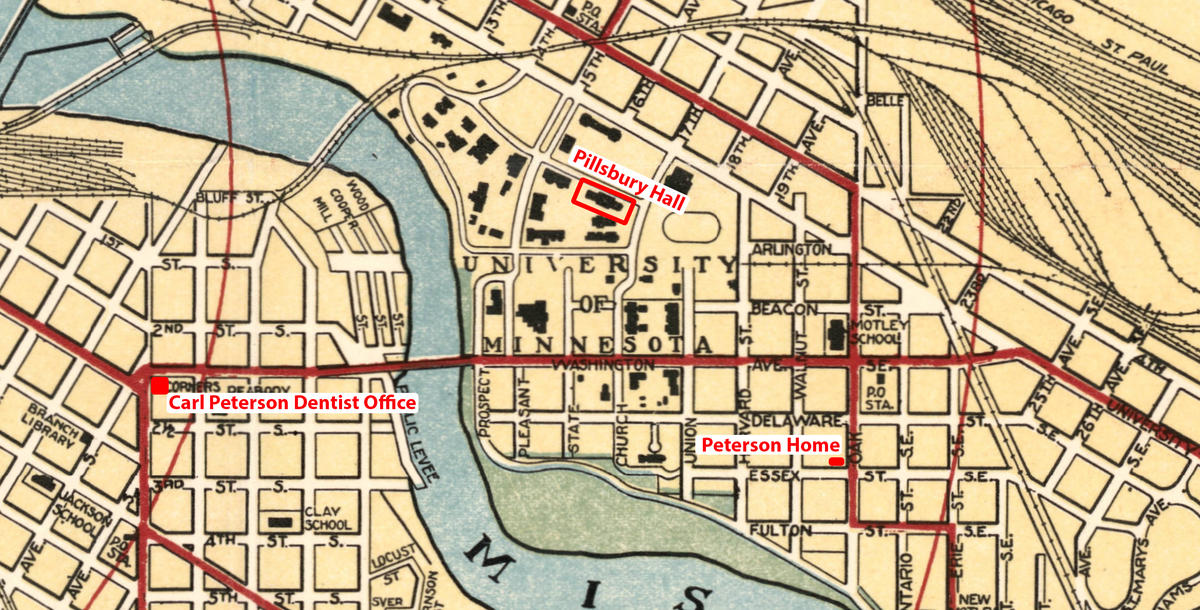

While successful in Cashton, Carl and Mattie wanted better educational opportunities for their children so they moved to Minneapolis in 1915. At first the family moved into the outskirts of the city’s lake district, but Carl opened a dental practice at 221 Cedar Avenue, just to the west of the University of Minnesota where he also employed Eunice as an office assistant. According to her daughter, Ruth Garrett Millikan, Eunice taught herself to play piano and had voice lessons in high school. She wanted to go to a music conservatory, but Eunice felt she could not justify asking for the extra expense with three siblings to follow. So, she attended the more affordable University of Minnesota. In a remarkable show of support, the family relocated to 420 Oak Street just to the east of the university, so Eunice could walk to campus. With her musical interests and caretaker tendencies, Eunice was active in the Women’s Glee Club and a variety of social organizations dedicated to improving student campus life. She joined the Young Women’s Christian Association, Women's Self Government Association, as well as three service societies (Pinafore, Tam O'Shanter, & Bib and Tucker). Yet, Eunice still found time to play women's baseball, a testimony to her remarkable energy and drive.

1920 map of the University of Minnesota area with Pillsbury Hall (home of the Geology Department, Peterson home and Peterson dental practice locations.

Eunice Peterson in 1923 University of Minnesota Glee Club.

Eunice Peterson photograph in 1922 Gopher (Volume 35).

At the ‘U’

Like many of our recent majors, Eunice did not enter the university expecting to complete a geology major. Millikan remembers that Eunice’s first geology connection occurred when she was in the library filling out her sophomore schedule. When another student mentioned her introductory geology class had been interesting, Eunice decided to sign up for it, and that impromptu decision would decide Eunice’s career.

In 1922, Peterson completed her bachelor's degree with a major in geology and a minor in paleontology. She was only the third woman to earn a bachelor’s degree in geology from the University of Minnesota. Elizabeth D. Bell was the first in 1906, and Mildred A. Hunter became the second in 1907.

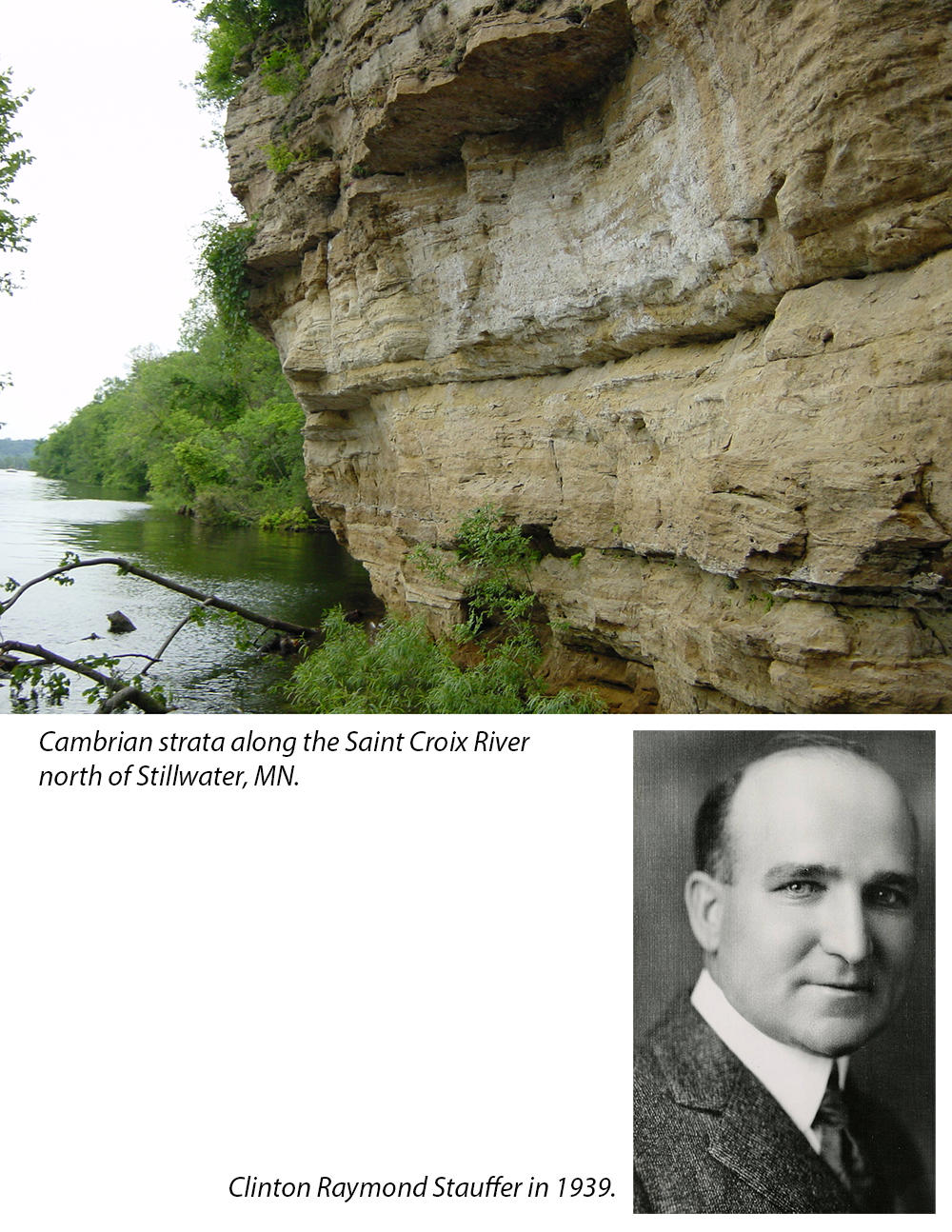

Although Eunice’s course work was exemplary and earned her membership in Sigma Xi, Eunice particularly loved field experiences. She mapped the Devil’s Lake region of Wisconsin and attended multiple field trips to the Iron Range and across Minnesota. Although one newspaper reporter would later write that Eunice was a retiring individual who preferred long tramps in the hills to talking of her exploits, she was bold in terms of finding new opportunities and taking on challenges. After graduation, Eunice engaged in postgraduate and field work at the University of Chicago. During the 1922-23 academic year, she taught as an Assistant in Geology at Ohio's Oberlin College and Conservatory, before she returned for a master’s program at Minnesota. Despite it being highly usual for women to undertake geologic fieldwork at the time, Eunice’s had her family’s full support. When Eunice mapped the Cambrian Geology of the Lower St. Croix Valley, camping out in the open, her mother, Mattie, accompanied Eunice for much of the summer as her field assistant. In 1924, Eunice became the first woman to earn a master’s degree in geology at the University of Minnesota. She completed her degree under the direction of Clinton Raymond Stauffer. It would be another eight years before a second woman, Jane Titcomb, also working with Stauffer, became the second woman to earn a master’s in geology. Only four women would achieve that goal in the half century after Eunice.

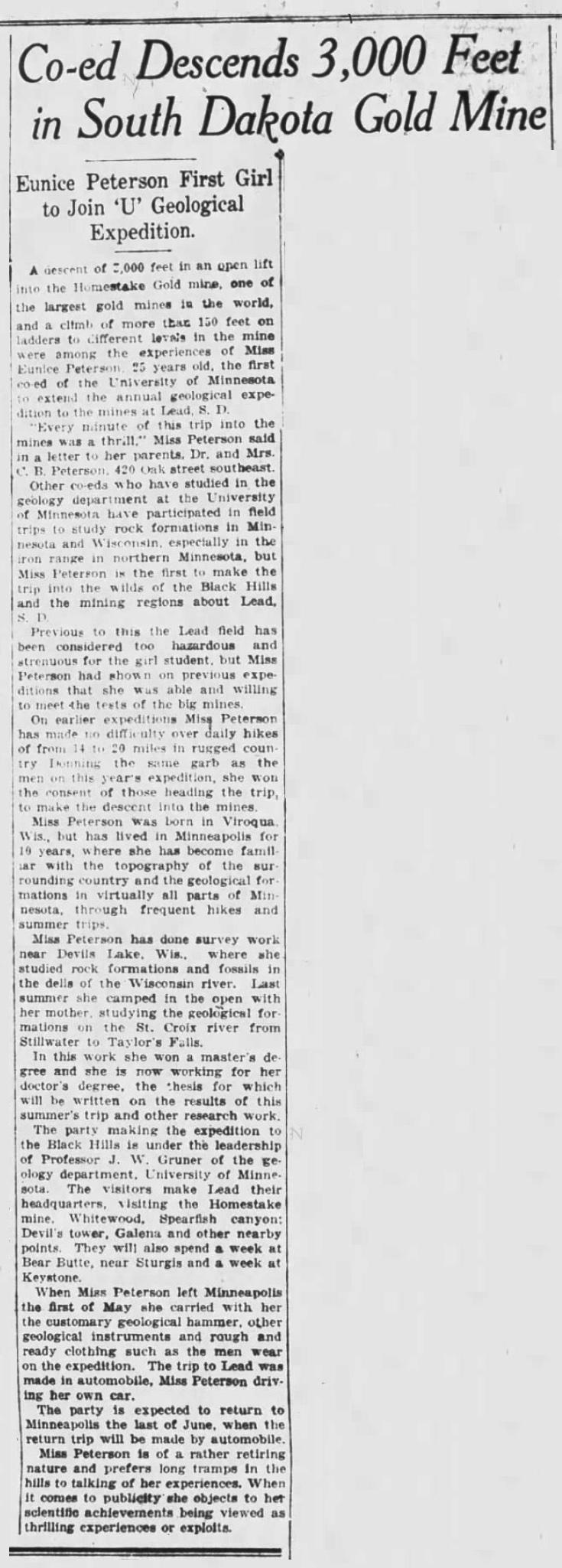

Despite her extensive field experience, when Eunice began her doctorate, she was dismayed to discover the department would not allow her to attend a summer-long field trip to the Black Hills. The trips, with their steep hikes and outdoor tent camping were considered too arduous for women. However, when she learned the 1925 Black Hills trip led by John Walter Gruner was short of vehicles, Eunice offered her father’s car as a vehicle – but with the provision that she was the only one allowed to drive the car (Millikan, personal communication). Gruner was forced to accept, and consequently, Eunice became the first woman to participate in the University’s Black Hills field trips. The Minneapolis Morning Tribune even covered her subsequent descent into the Homestake Mine – as people were captivated by the idea of a coed competing in a male-dominated, field-oriented science. The reporter wrote that “Miss Peterson… objects to her scientific achievements being viewed as thrilling experiences or exploits” but only after having just reported them as such.

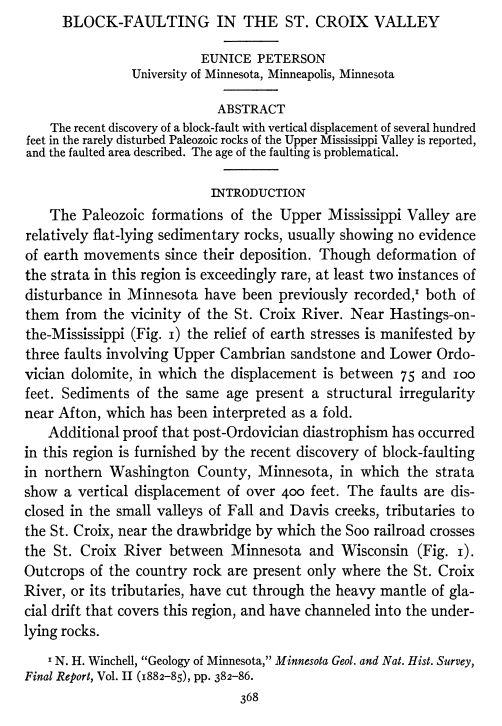

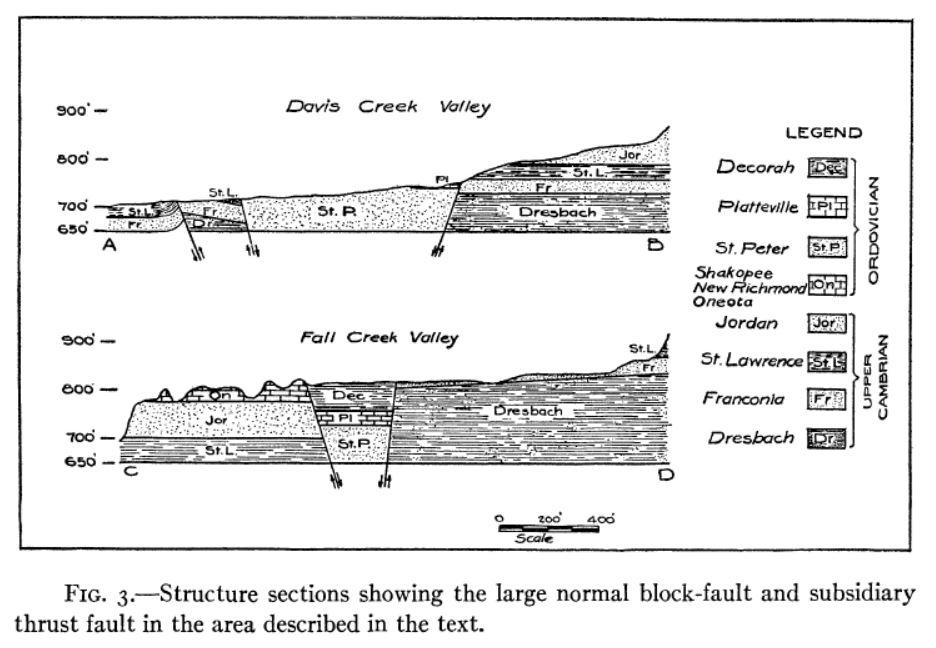

Eunice completed her Ph.D. in 1927 under Stauffer’s guidance, mapping the Dresbach Formation of Minnesota. A front-page story in the Star Tribune covering the university’s December graduation ceremony mentioned there were six students earning their Ph.D. Of those six, only Peterson was listed by name, as the first woman to earn a Doctor of Philosophy degree in geology. Other newspapers in Albert Lea and Austin, Minnesota covered her achievement. Yet, that same year also saw the first professional attack on her competence. While completing her masters’ fieldwork, Eunice discovered faults, which at the time were unexpected in what was presumed to be a stable, tectonically inactive area, and redefined the extent of some geological formations. Her discoveries drew the wrath of Fredrick Sardeson, who had been the third geology professor at the University of Minnesota but was later sacked because of his inability to get along with colleagues.

Image of faulting from Peterson's 1927 publication - Block Faulting in the St. Croix Valley

A Challenge

Sardeson, with a chip on his shoulder towards the department that dismissed him in 1914, attacked Eunice’s first publication in an 8-page paper he titled “Block-faulting on the grand prairies?” Perceiving Peterson’s work as a refutation of his own work, Sardeson not only accused Peterson of misinterpreting the region’s geology, but of mapping imaginary faults – a direct challenge to her field abilities. Sardeson revealed his underlying misogyny when he wrote that he did not interpret her perceived errors as an indication of perversity on the author’s part but that they were the product of “a maiden effort of the student to be orthodox, geologically.” [bold font added]

It was not until 1959 that another Minnesota professor, Robert E. Sloan, restudied the area to find that Peterson was correct and Sardeson wrong. Although Peterson was vindicated, Sardeson’s attack remained unchallenged until a year after his death. Sardeson had been the acknowledged authority on the Lower Paleozoic rocks of Minnesota - yet in her fieldwork, Peterson had proved herself to be the superior of one of the region’s greatest stratigraphers.

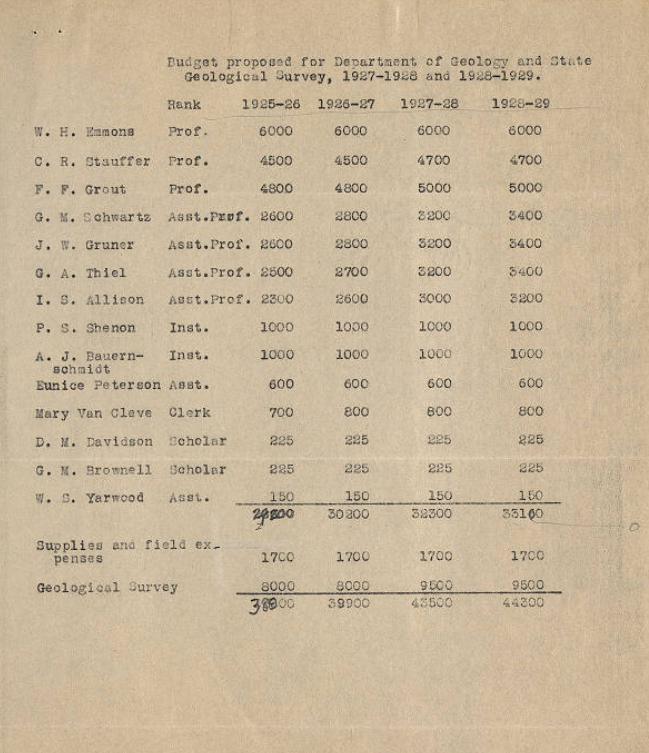

Image of department of Geology's 1925 budget sheet with Peterson's appointment listed.

Even before she finished her doctorate, Eunice quietly broke yet another barrier. In 1924, she was the first woman hired by the Geology Department and Minnesota Geological Survey as a professional geologist.[1] Eunice appears in the department budgets from 1924 to 1927 as an Assistant Geologist. Although her $600 salary was low compared to Gruner’s $2,600 Assistant Professor stipend, it matched that of other male assistant geologists. Previously the only woman employed by the department had been Mary Van Cleve, who guided the department as its clerk/secretary through its first few decades. Eunice’s duties included managing the Winchell Library of Geology in Pillsbury Hall for three years, which provided valuable experience she would build upon after leaving Minnesota.

[1]Although Elizabeth D. Bell and Milard A. Hunter were earlier appointed Assistants by the University, in 1907. At her death, Hunter left a bequest to fund a scholarship that is still active at the University.

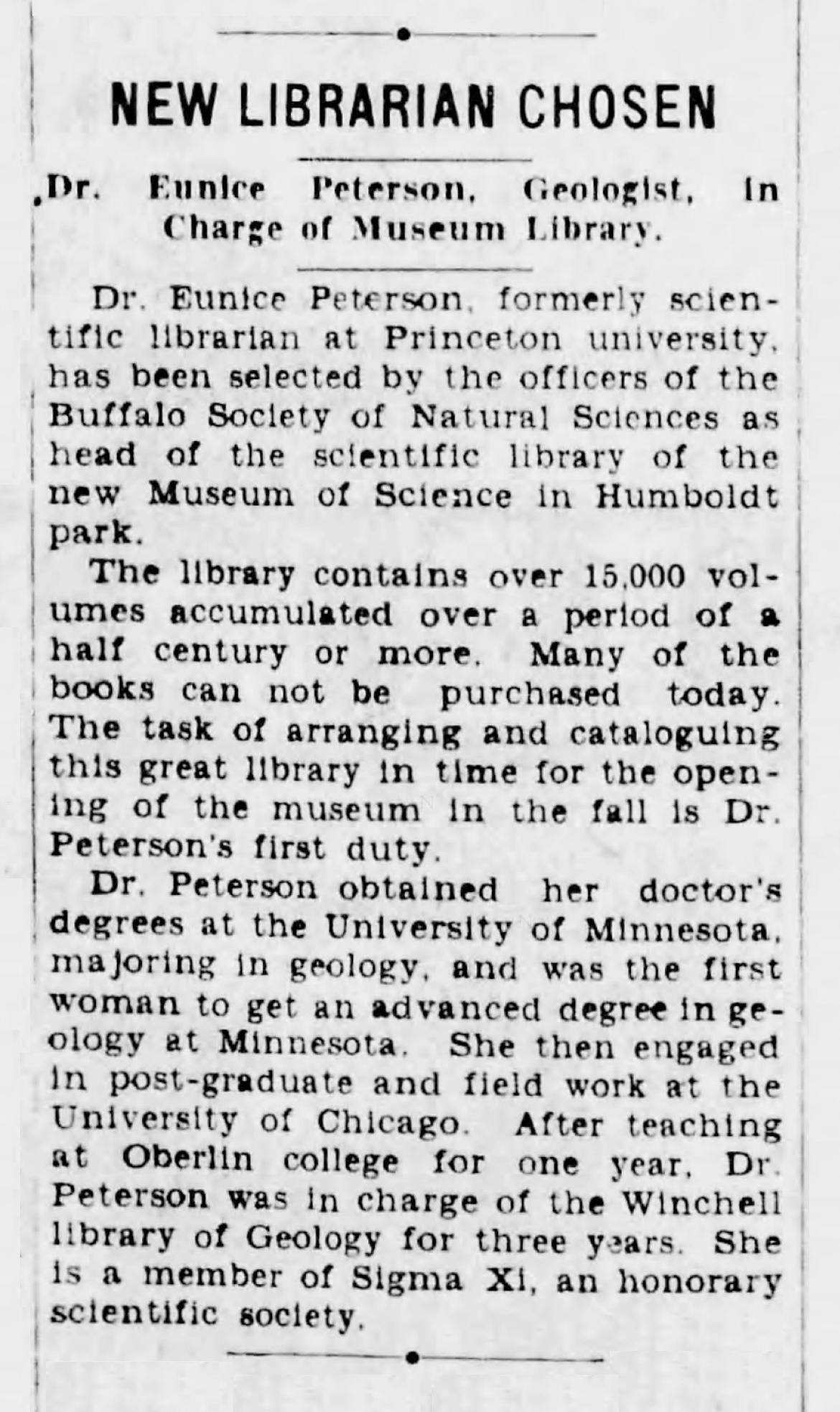

Buffalo Evening News article on Peterson's appointment to Buffalo Science Museum - May14, 1928

After the ‘U’

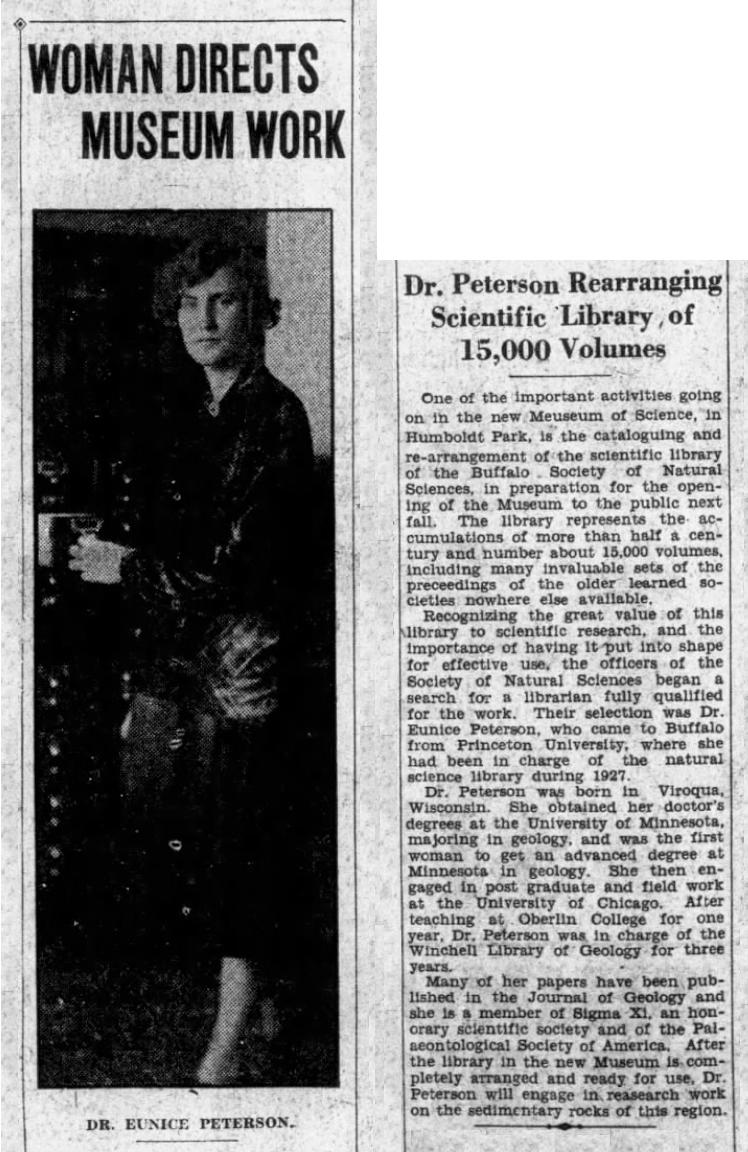

After completing her doctorate, Eunice spent a brief time at Princeton University in New Jersey curating their mineral and fossil collection and taking charge of the natural science library there. Then she moved to Buffalo, New York to oversee the scientific library of the Buffalo Society of Natural Sciences in their newly opened Museum of Science. She became the museum’s Research Librarian and Assistant Curator of Paleontology. Buffalo newspapers reveled in the novelty of having hired a woman with a doctorate in geology. Their articles emphasized Peterson’s many publications in the Journal of Geology and her membership in the Paleontological Society of America. They reported that once she wrangled the library in line, Peterson would embark on field research of the region’s sedimentary rocks.

Buffalo Times article on Peterson's appointment to Buffalo Science Museum - May 13, 1928. link to article text

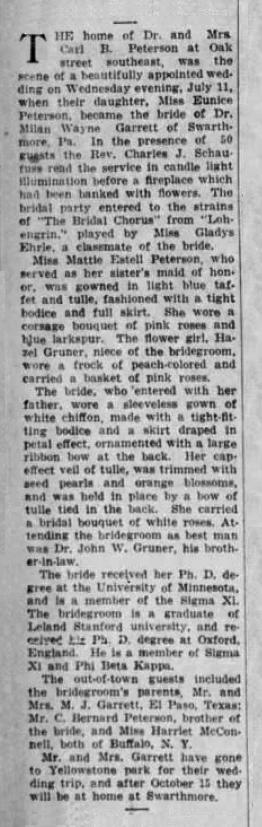

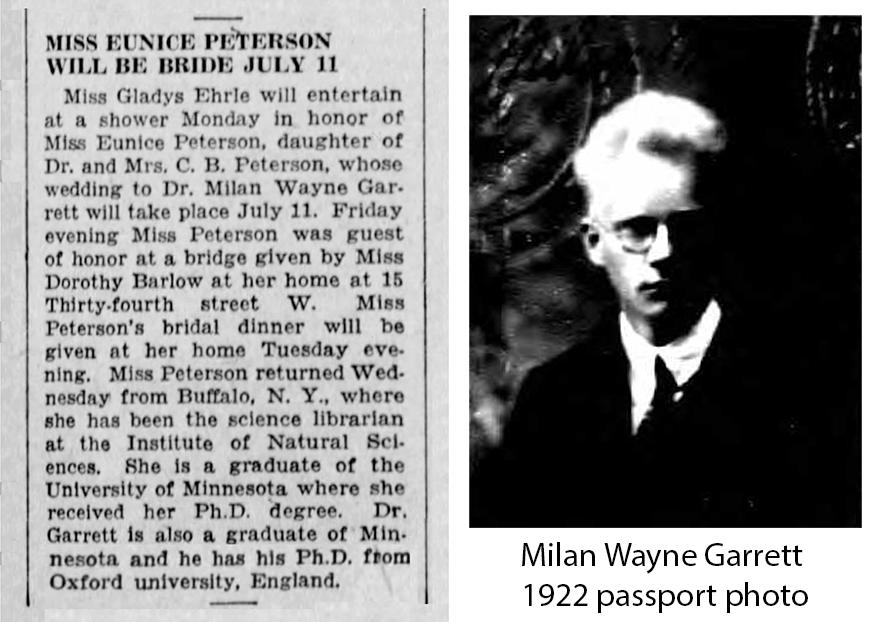

However, personal developments derailed her planned research. Eunice’s 1925 Black Hills field trip and the resulting connection with Gruner proved fortuitous. As it was through Gruner’s wife, Opal Garrett, that Eunice met and eventually married Gruner’s brother-in-law, (Milan) Wayne Garrett. Wayne was a few months younger than Eunice. He was born in Helena, Montana on December 15, 1900, to two schoolteachers who, like Eunice’s parents, prioritized their children’s education. Wayne’s family moved to the Philippines when he was two and did not return to the United States until 1910 when they moved to El Paso, Texas. Even then, Wayne’s mother continued to tutor him until his high school junior year. Her tutoring must have been effective as Wayne attended California’s Leland Stanford Junior University and then went to England’s Oxford University as a Rhoades Scholar, earning a doctorate in physics. At Eunice and Wayne’s wedding on July 11, 1928, John Gruner was Wayne’s best man, Eunice’s sister, Mattie Estelle was her maid of honor, and John and Opal’s three-year old daughter, Hazel, was the flower girl. Newspapers in Minneapolis and El Paso described the marriage in detail. For their honeymoon, Eunice and Wayne appropriately chose an extended stay at Yellowstone National Park, followed by a cross country tour of other geologic locations.

Peterson-Garrett wedding announcement in the Minneapolis Star - July 7, 1928 with Milan Wayne Garrett's 1922 passport photo.

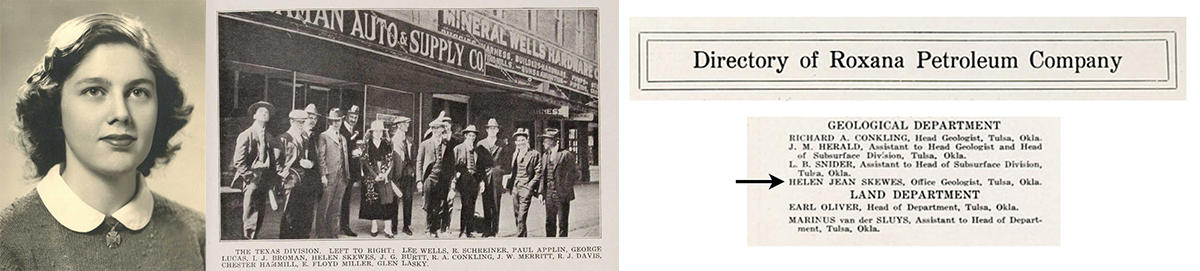

Eunice’s marriage jeopardized her professional plans. At the time, social strictures made it extraordinarily difficult for married women to pursue any career, much less one in science. In 1917, Helen Jean Skewes, a paleontologist who would later collaborate with Stauffer on many publications, was the first woman to be employed as a geologist in the U.S. oil industry. Her petroleum career ended a year later when she married Frederick Byron Plummer. Roxanne Petroleum, like most companies of the time, did not employ married women. Consequently, after her marriage Helen Plummer could only work as a consultant.

Helen Skewes Plummer at an early age and seen with Texas Division of Roxanne Petroleum in 1917. Images courtesy of the Museum of the Earth, Ithaca, New York.

Similarly, Eunice’s marriage significantly curtailed her professional career. Eunice moved to Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania where Wayne taught, ending her time at the Buffalo Museum of Science. From 1929-30, Eunice was a demonstrator in geology at nearby Bryn Mawr College, a women's liberal arts college. However, the arrival of two daughters, Sadie in 1931 and Ruth in 1933, further limited her professional aspirations. Yet, Eunice would not give up geology entirely. From 1931 to 1938, she worked part time as a paleontologist on the scientific staff of Biological Abstracts in Philadelphia, translating abstracts. Starting in 1938 she worked as a librarian and editor for the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, and Eunice retained her membership in the Paleontological Society well into the late 1940s. At age 50, Eunice earned a degree in library science and then worked as a research librarian at Foote Mineral Company until Pennsylvania law forced her to retire at age 62. At the time, the state’s mandatory retirement law allowed men to work until age 65.

After their retirement, Eunice and Wayne spent some years at the National Oak Ridge Laboratory before moving to Severna Park, Maryland where their daughter Sadie lived. Eunice died on June 18, 1988, and Wayne on January 27, 1992. They were buried next to Eunice’s parents and brother in the family plot back in Viroqua, Wisconsin.

Legacies

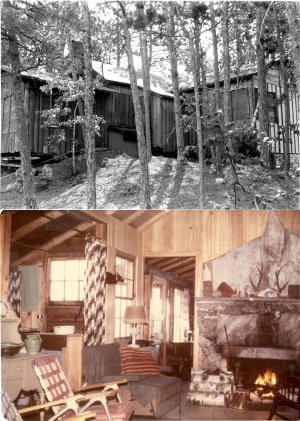

A year after Eunice and Wayne’s marriage, Eunice’s parents, Carl and Mattie, had built a cabin on a small island at Rainy Lake on land they had bought years earlier. Eunice and Wayne spent every summer for the next 57 years at the cabin and John and Opal Gruner built another cabin on a nearby island so the two families could spend their summers together. The surrounding land became part of Voyagers’ National Park in 1975, but Eunice’s family continued to spend time at the cabin until 1992. The cabin, now a National Heritage building, is held in trust by the park. But it is another legacy that matters here.

In 1927, Eunice Peterson opened a door for Minnesota women in geology. It would be almost two decades (1946) before another woman, Margaret Skillman, earned a Ph.D. in geology at Minnesota, with the third being Susan Williams in 1977. In 1980, Anita Crews became the first female professor in the department, followed by Emi Ito in 1982, and Karen Kleinsphen in 1984. In 1997, Donna Whitney joined the department and in 2012, she became the first woman department chair in the College of Science and Engineering.

For the past few decades, women have outnumbered men in our Ph.D. graduate program, sometimes by a 2:1 ratio. Yet, our current faculty roster, while easily the most diverse in our department’s history, is still only 33% female. And we only achieved that milestone in 2024. Consequently, we still have a long way to go before we can justly claim that Earth and Environmental Sciences are open to all. The progress we have made is the result of women who were willing to challenge the conventions of their time and lead the way for those who followed.

For our department, Eunice Peterson was the one who started us on that path.

Any comments, concerns, or suggestions?

email: Kent Kirkby ([email protected])

Acknowledgements & Sources:

All family and personal stories or information on Eunice Peterson Garrett, as well as her college-age portrait were generously given by her daughter, Ruth Garrett Millikan, who extended her mother’s academic trailblazing into other fields. Millikan, now professor emerita of Philosophy at the University of Connecticut, is a leading philosopher of biology, psychology, and language, who pioneered the concept of biosemantics.

Additional Information came from:

University of Minnesota Archives – The Gopher (annual yearbook of the University of Minnesota), Department of Geology Budget Papers, images of UMN faculty members.

Newspaper articles from Minneapolis Tribune, Minneapolis Star, and Buffalo Evening News

United States Census records

Minneapolis City Directories