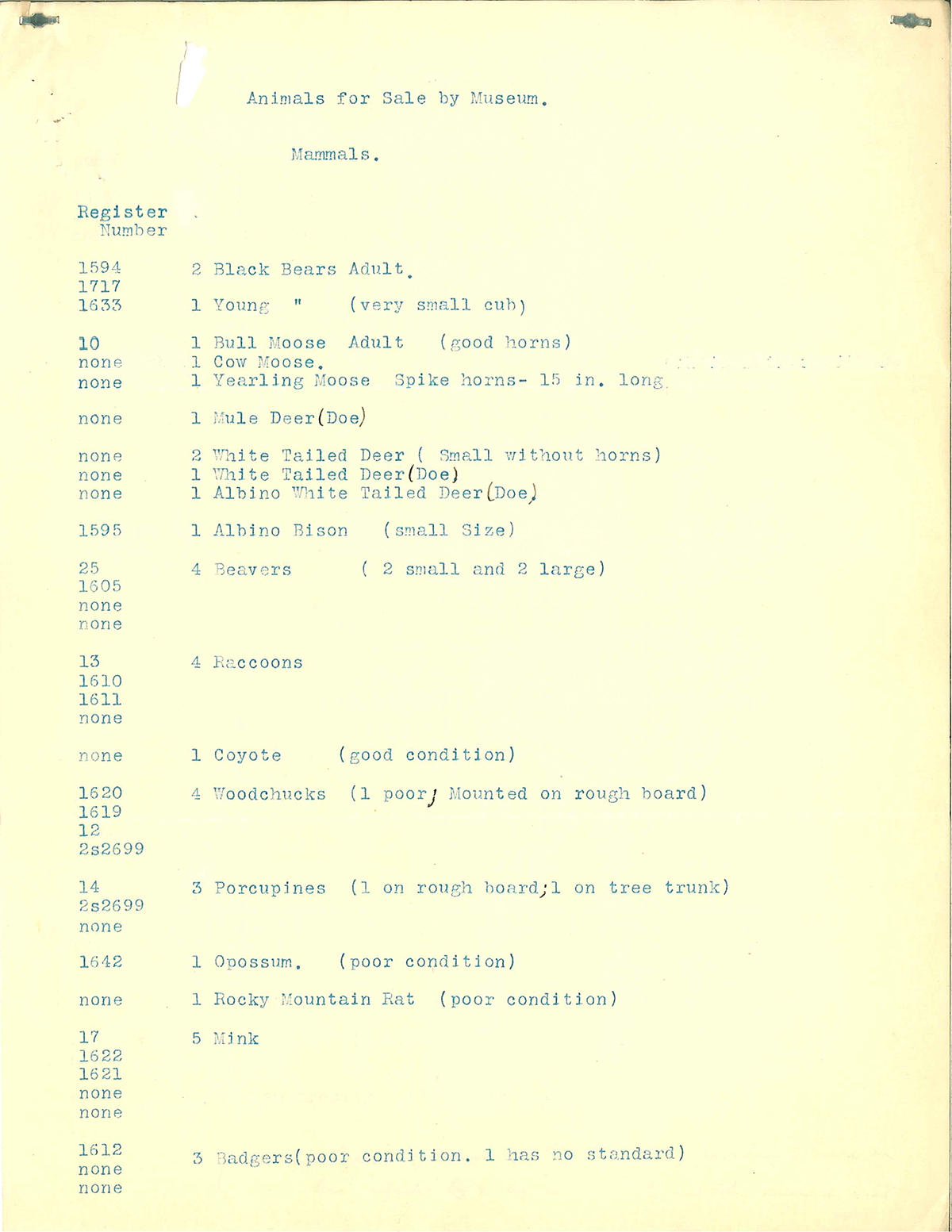

Rebecca Toov of the University of Minnesota’s Archives gathered a documentary treasure trove on Cardigan. While copies of the Tribune series were included, other documents disprove the articles’ crafted tales. Cardigan’s mount was discarded six years before the articles were written rather than two. More importantly, Cardigan was not the only taxidermy mount Thomas Sadler Roberts wished to dispose of. Cardigan was just one of sixty-nine mounts tossed out, including a white buffalo calf originally donated by John Sargeant Pillsbury in 1885.

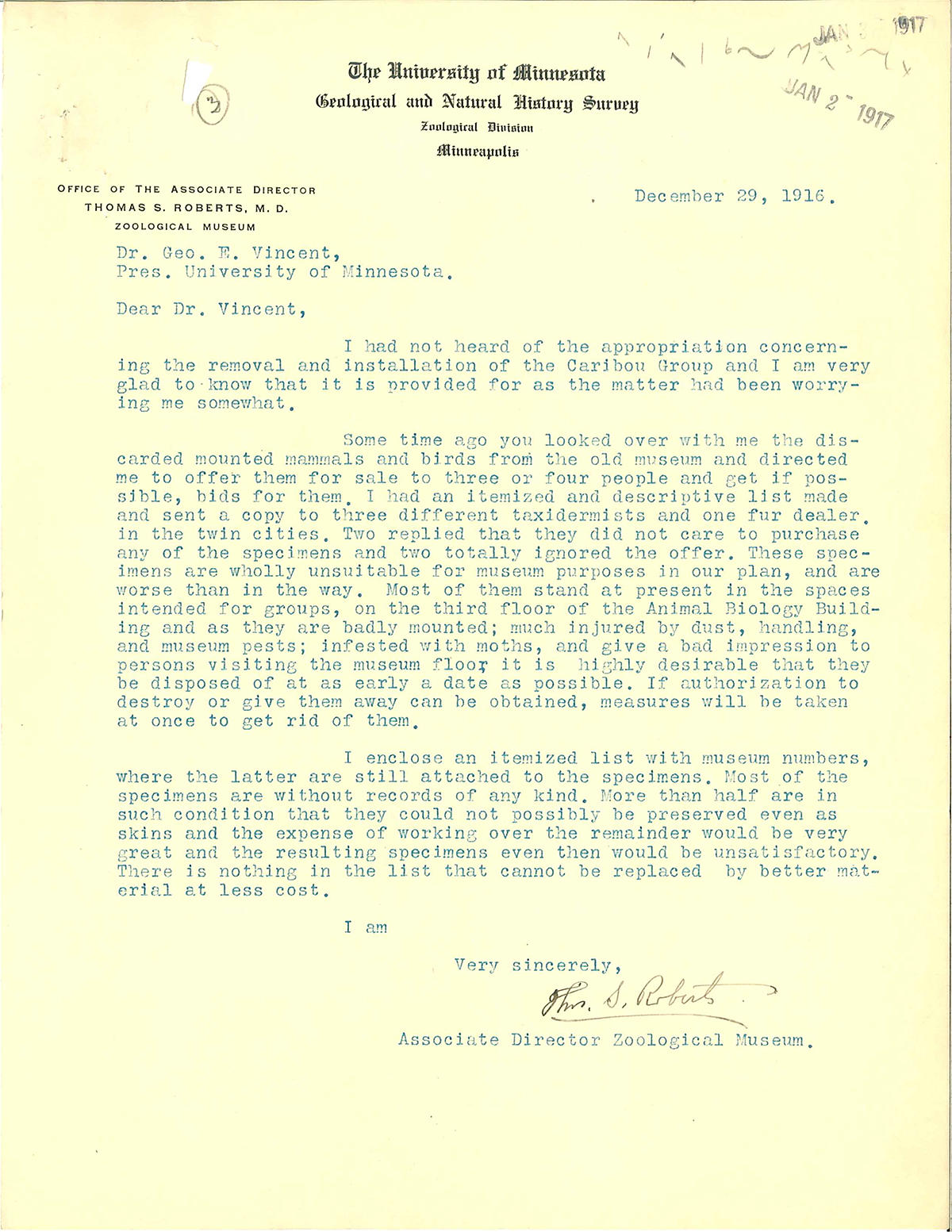

It was not an impulsive decision to dispose of these specimens and was one that required the approval of the university regents. In a letter sent to George E. Vincent, then University President, Roberts wrote:

“Some time ago you looked over with me the discarded mounted mammals and birds from the old museum and directed me to offer them for sale to three or four people and get if possible, bids for them. I had an itemized and descriptive list made and sent a copy to the three different taxidermists and one fur dealer in the twin cities. Two replied that they did not care to purchase any of the specimens and two totally ignored the offer. These specimens are wholly unsuitable for museum purposes in our plan, and are worse than in the way. Most of them stand at present in the spaces intended for groups, on the third floor of the Animal Biology Building and as they are badly mounted; much injured by dust, handling, and museum pests; infested with moths, and give a bad impression to persons visiting the museum floor it is highly desirable that they be disposed of at as early a date as possible. If authorization to destroy or give them away can be obtained, measures will be taken at once to get rid of them….”

… “Most of the specimens are without records of any kind. More than half are in such condition that they could not possibly be preserved even as skins and the expense of working over the remainder would be very great and the resulting specimens even then would be unsatisfactory. There is nothing in the list that cannot be replaced by better material at less cost.”

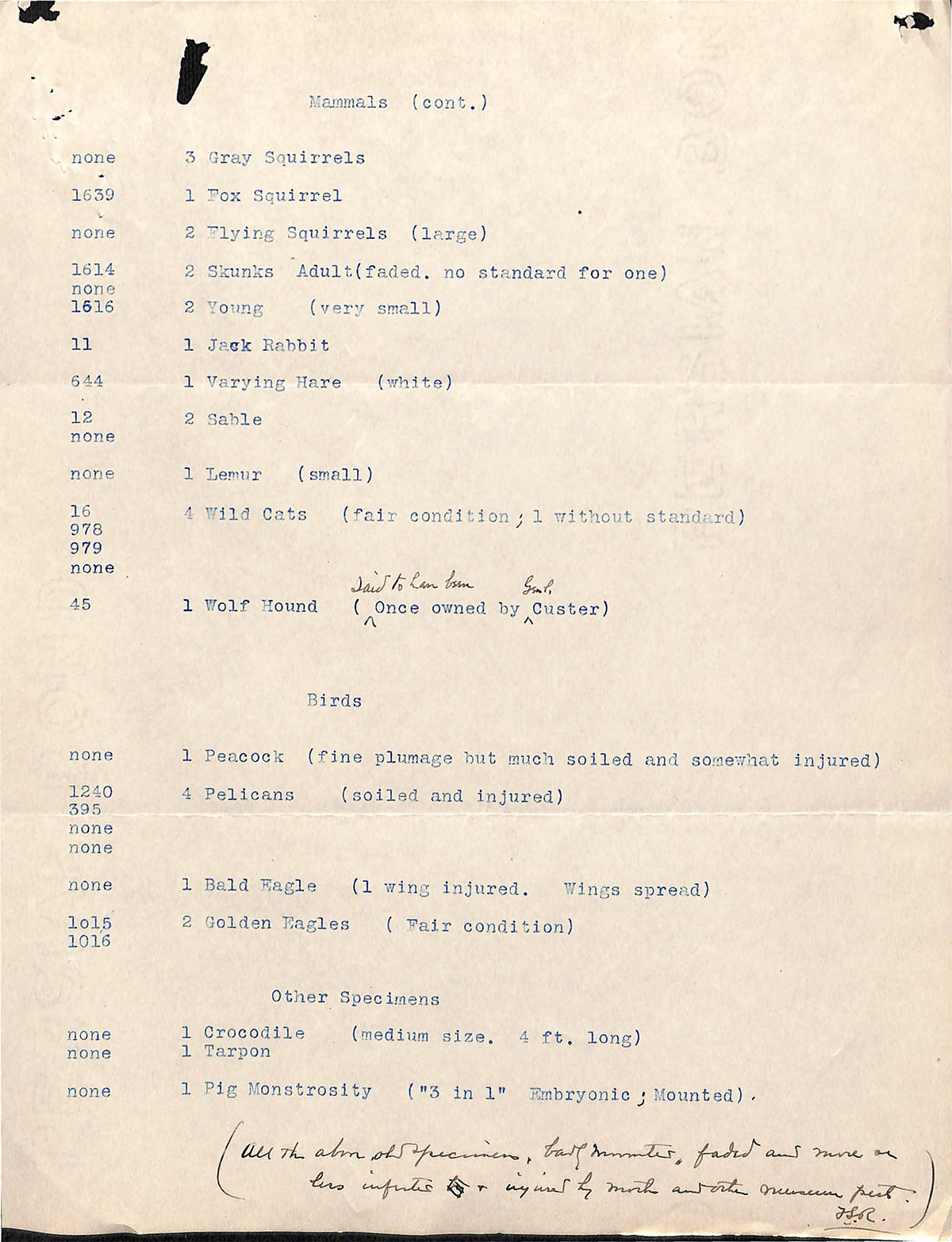

Roberts accompanied his request with a typed list of the sixty-nine specimens, with two additions written in his own hand, intended to sway the regents’ decision. At the bottom of the second page, Roberts wrote “(all the above specimens, badly mounted, faded and more or less infected + injured by moths and other museum pests. - TSR).” Cardigan though, warranted a specific line. The typewritten list identified Cardigan as item ’45 - 1 Wolf Hound (once owned by Custer)'. In pen, Roberts modified the latter clause to read as ‘(Said to have been once owned by Genl. Custer)’ probably to cast doubt on Cardigan's identity to forestall any history-minded regent from halting Cardigan's disposal. The handwritten notes were not included with the list sent out earlier to potential buyers but were added to the regents’ copy.

List of museum mounts for disposal from Zoological Museum - page 1

List of museum mounts for disposal from Zoological Museum - page 2

Roberts’ desire to get rid of Cardigan and the other mounts was not solely based on their appearance or evolving museum standards but was also personal. The infested mounts were a risk to the museum’s other holdings, including an immense collection of bird skins Roberts himself had begun acquiring while still in high school. Roberts’ family moved to Minnesota from Pennsylvania because his father, like Cassius Terry, suffered from tuberculosis and hoped Minnesota’s climate would improve his health. From age sixteen to eighteen, Roberts collected and preserved nearly six hundred bird specimens and he significantly increased that collection while in college. When he joined the university faculty, Roberts held off adding his bird skins to the old General Museum collections as he feared they would decay in the museum’s antiquated facilities. It was not until the biological collections were moved to a new Zoological Museum with better facilities that Roberts was comfortable adding his birds. Even then though, the old General Museum mounts posed a risk to his treasured bird skin collection. Hence, they had to go.

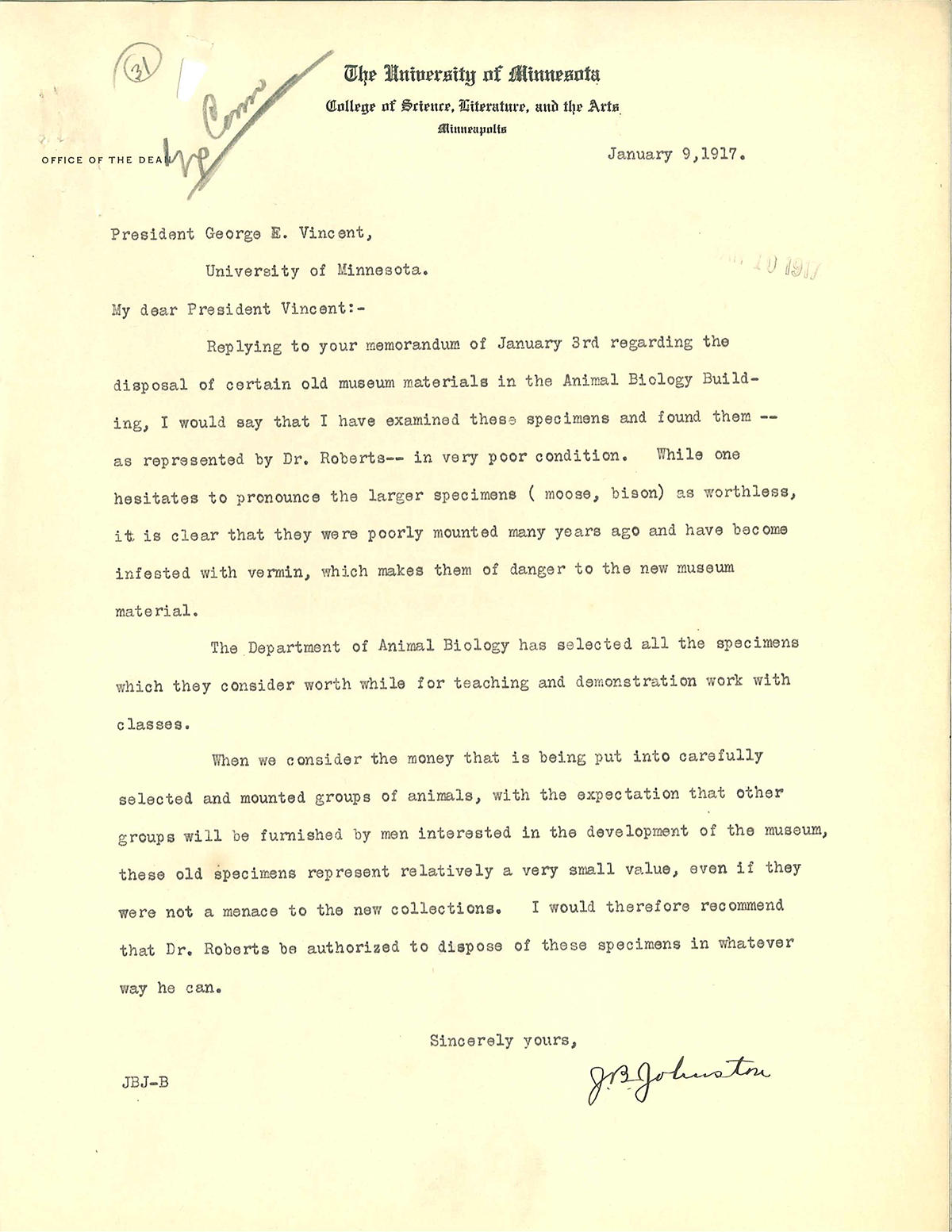

President Vincent asked Dean John Black Johnston to verify Roberts’ impression of the mounts. In his letter on January 9, 1917, Dean Johnston responded:

Replying to your memorandum of January 3rd regarding the disposal of certain old museum materials in the Animal Biology Building, I would say that I have examined these specimens and found them -- as represented by Dr. Roberts -- in very poor condition. While one hesitates to pronounce the larger specimens (moose, bison) as worthless, it is clear that they were poorly mounted many years ago and have become infested with vermin, which makes them of danger to the new museum material.

He concluded his letter with a recommendation “that Dr. Roberts be authorized to dispose of these specimens in whatever way he can.”

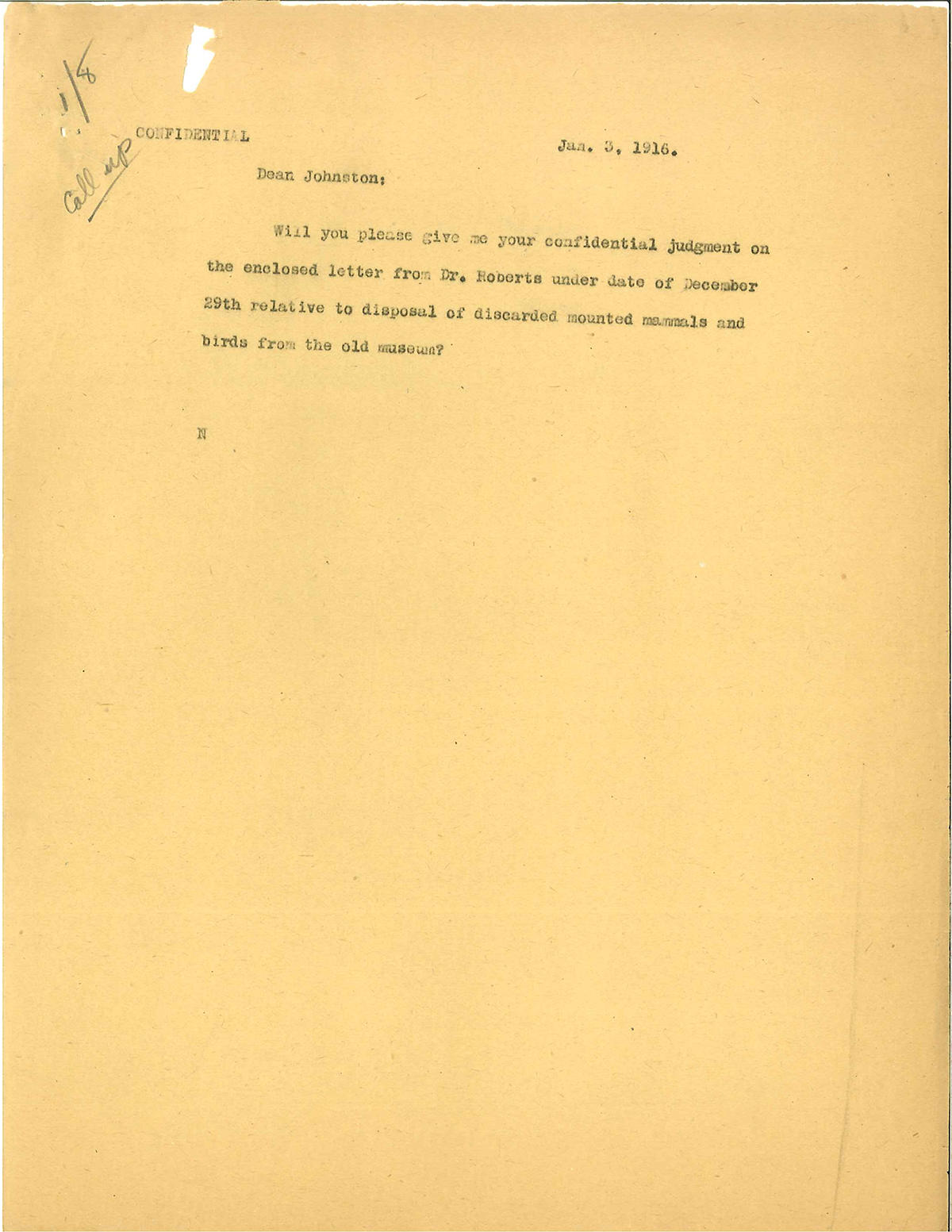

Note from President Vincent to Dean Johnston January 3 1917 (mistakenly noted as 1916 in heading)

Dean Johnstone response to President Vincent - January 9, 1917

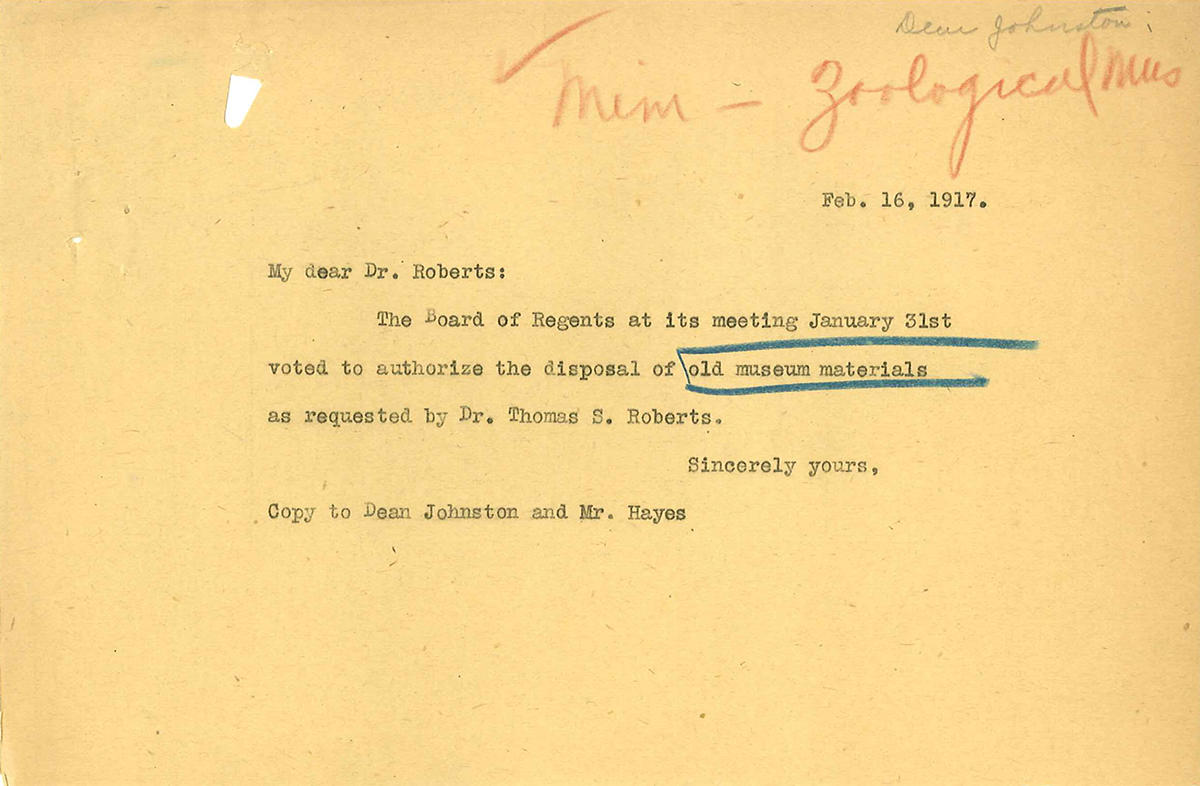

At the January 31, 1917, Board of Regents meeting, the Regents “Voted to authorize the disposal of old museum materials as requested by Dr. Thos S. Roberts.” On February 16, 1917, President Vincent forwarded that approval to Roberts and Cardigan most likely disappeared soon after, as Roberts had little reason to delay.

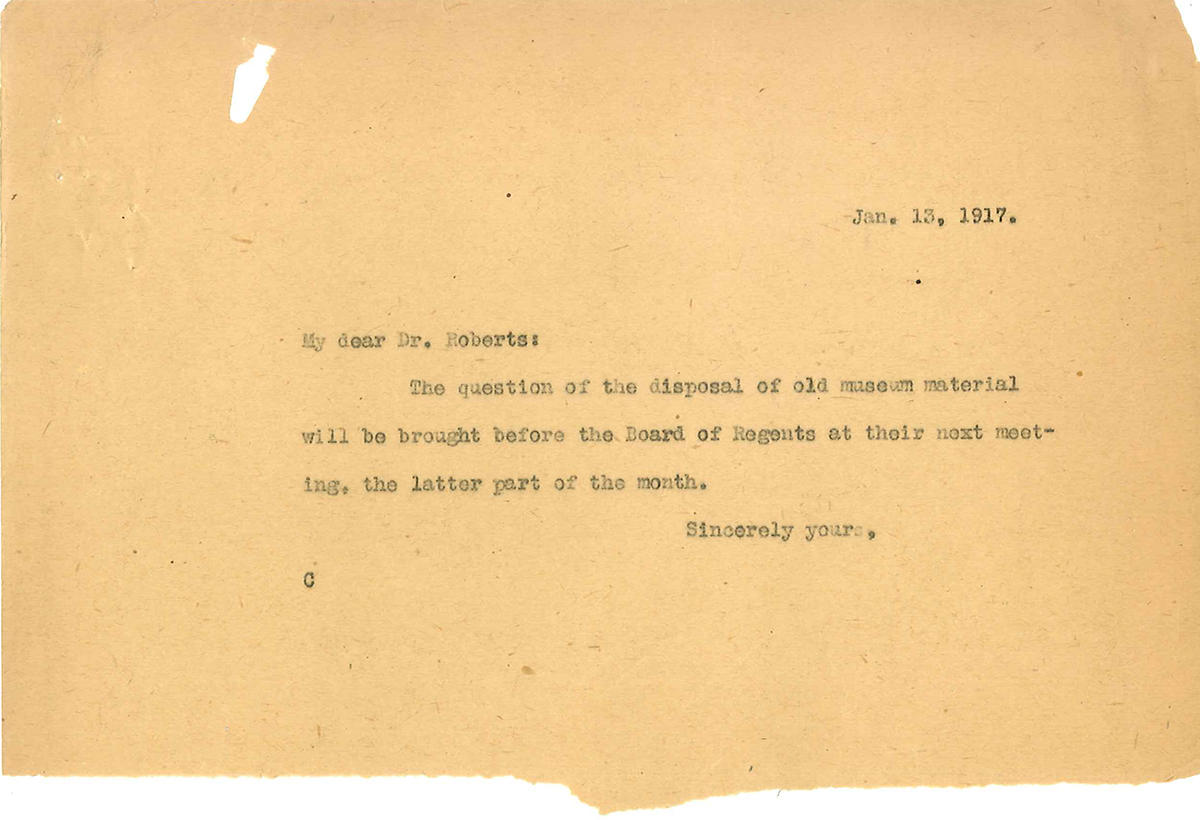

Note from President Vincent's to Roberts on Jan 13 1917

Note from President Vincent's to Roberts on February 16, 1917

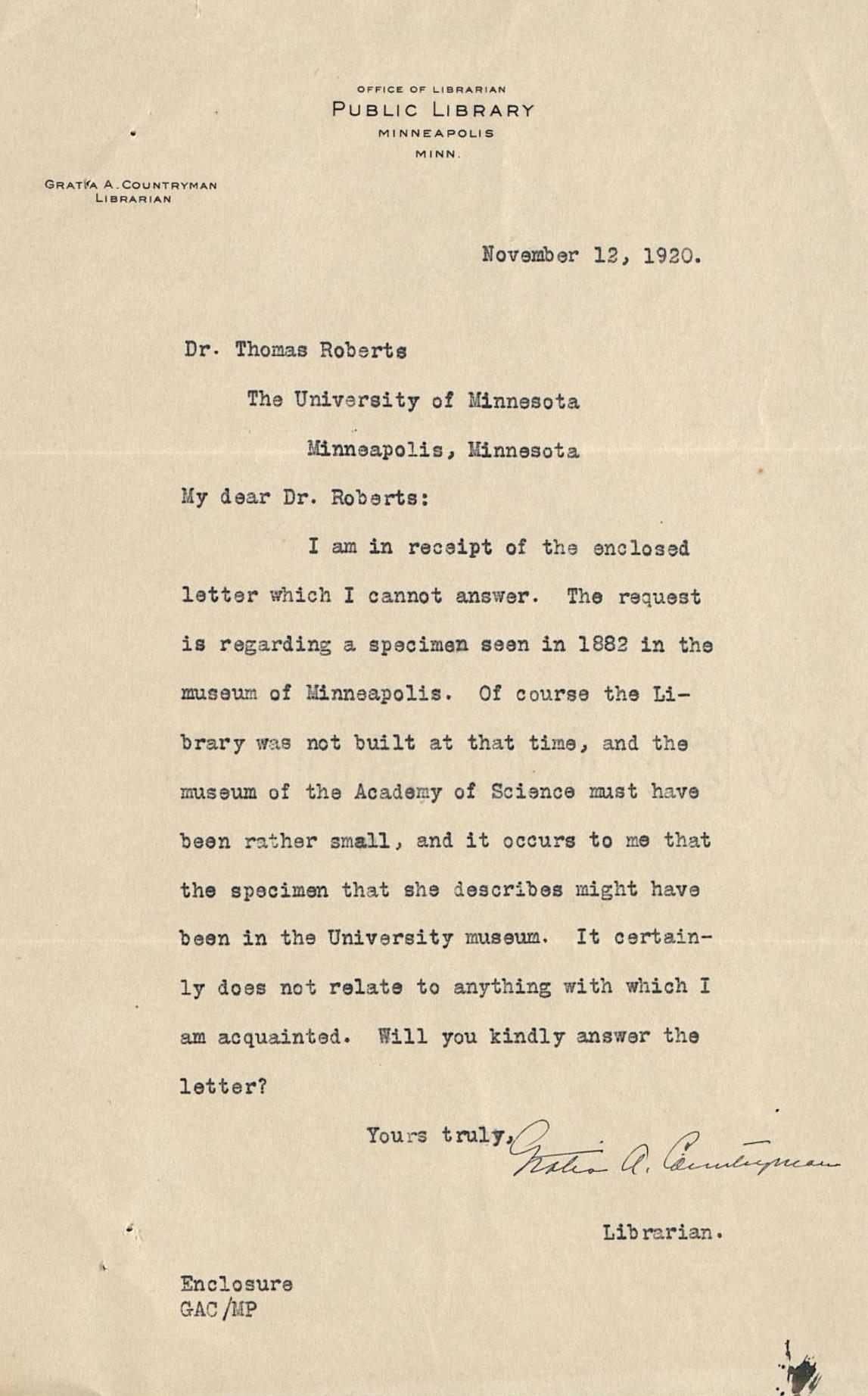

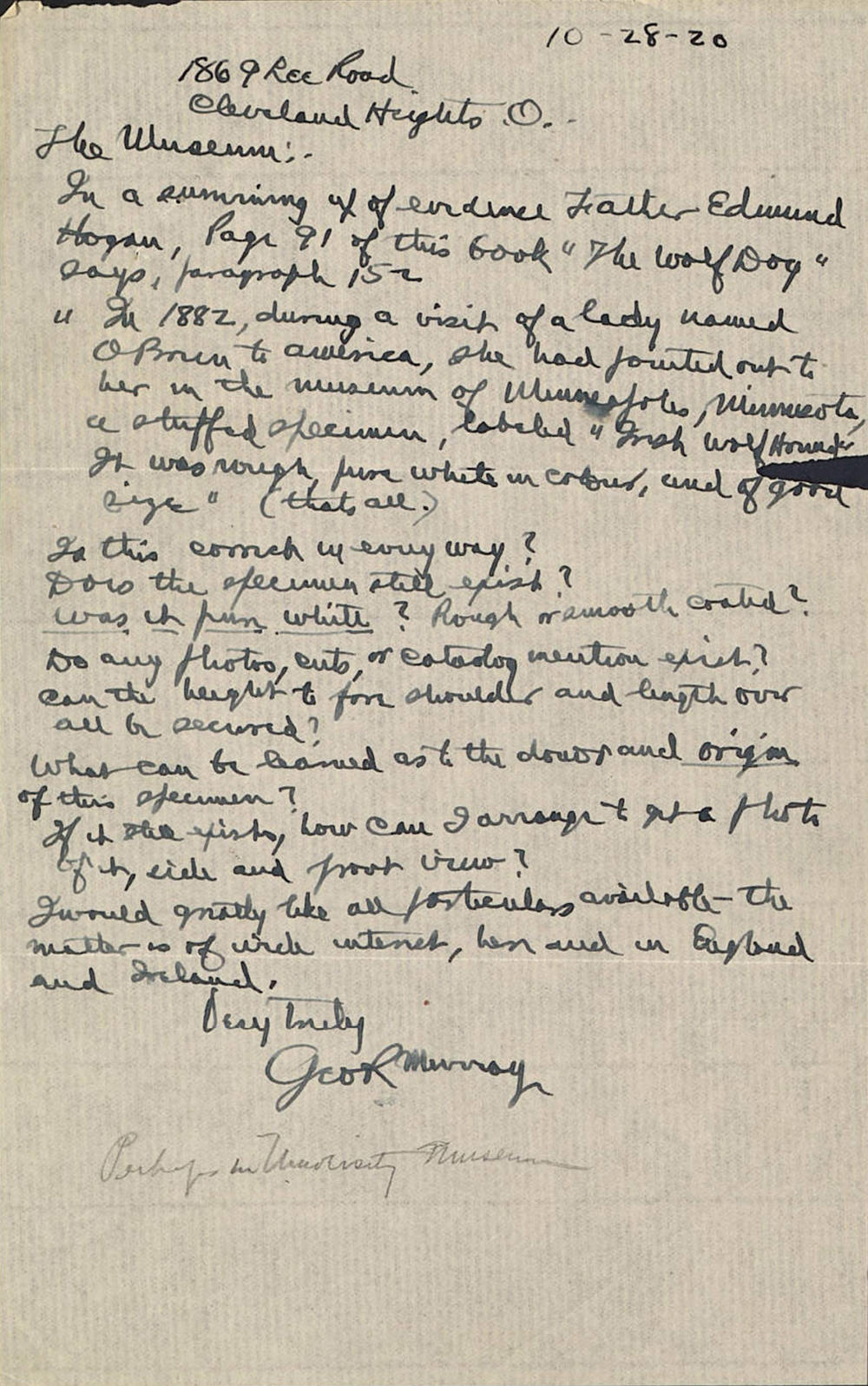

Less than four years later though, Roberts faced the repercussions of his decision with the first of Cardigan’s many seekers. In letters with Gratia Countryman, Minneapolis Librarian, and George R. Murray, a wolfhound enthusiast, Roberts had to defend his decision to dispose of Cardigan. Murray originally wrote Countryman because of rumors that Cardigan’s mount had been given to the Minnesota Academy of Sciences, a scientific society of the late 1800s whose small collection was given to the Minneapolis Library when the society temporarily folded. Murray was unaware of Cardigan’s identity but was simply trying to track down a museum display briefly mentioned in Father Edmund Hogan’s 1897 book, ‘The History of The Irish Wolfdog.’

In a summary of evidence ... Father Edmund Hogan, Page 91 of this book ‘The Wolf Dog’; says paragraph 15, ‘In 1882, during a visit of a lady named O’Brien to America, she had pointed out to her in the museum of Minneapolis, Minnesota, a stuffed specimen, labeled ‘Irish Wolfhound.’ It was rough, fur white in colour, and of good size.’

George R. Murray - October 28, 1920 – letter addressed to ‘The Museum.’

Letter from Countryman to Roberts - November 12, 1920

Portrait of Gratia Countryman in 1889

Letter from George Murray to "The Museum" that made its way to Gratia Countryman - dated October 28, 1920 (link to text)

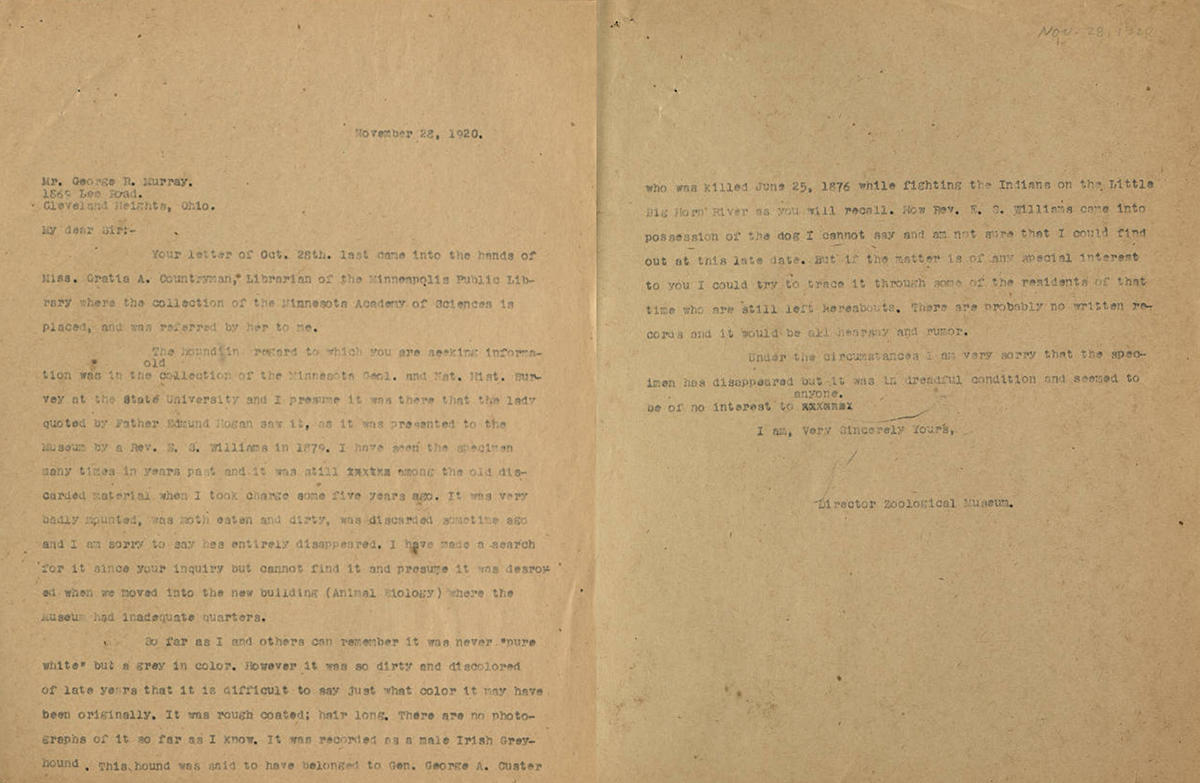

In his reply to Murray, Roberts wrote:

“I have seen the specimen many times in years past and it was still among the old discarded material when I took charge some five years ago. It was very badly mounted, was moth eaten and dirty, was discarded sometime ago and I am sorry to say has entirely disappeared. I have made a search for it since your inquiry but cannot find it and presume it was destroyed when we moved into the new building (Animal Biology) where the Museum had inadequate quarters.”

He ended the letter with the lines:

“Under the circumstances I am very sorry that the specimen has disappeared but it was in dreadful condition and seemed to be of no interest to anyone.”

Roberts' letter to George Murray on November 28, 1920 (link to text)

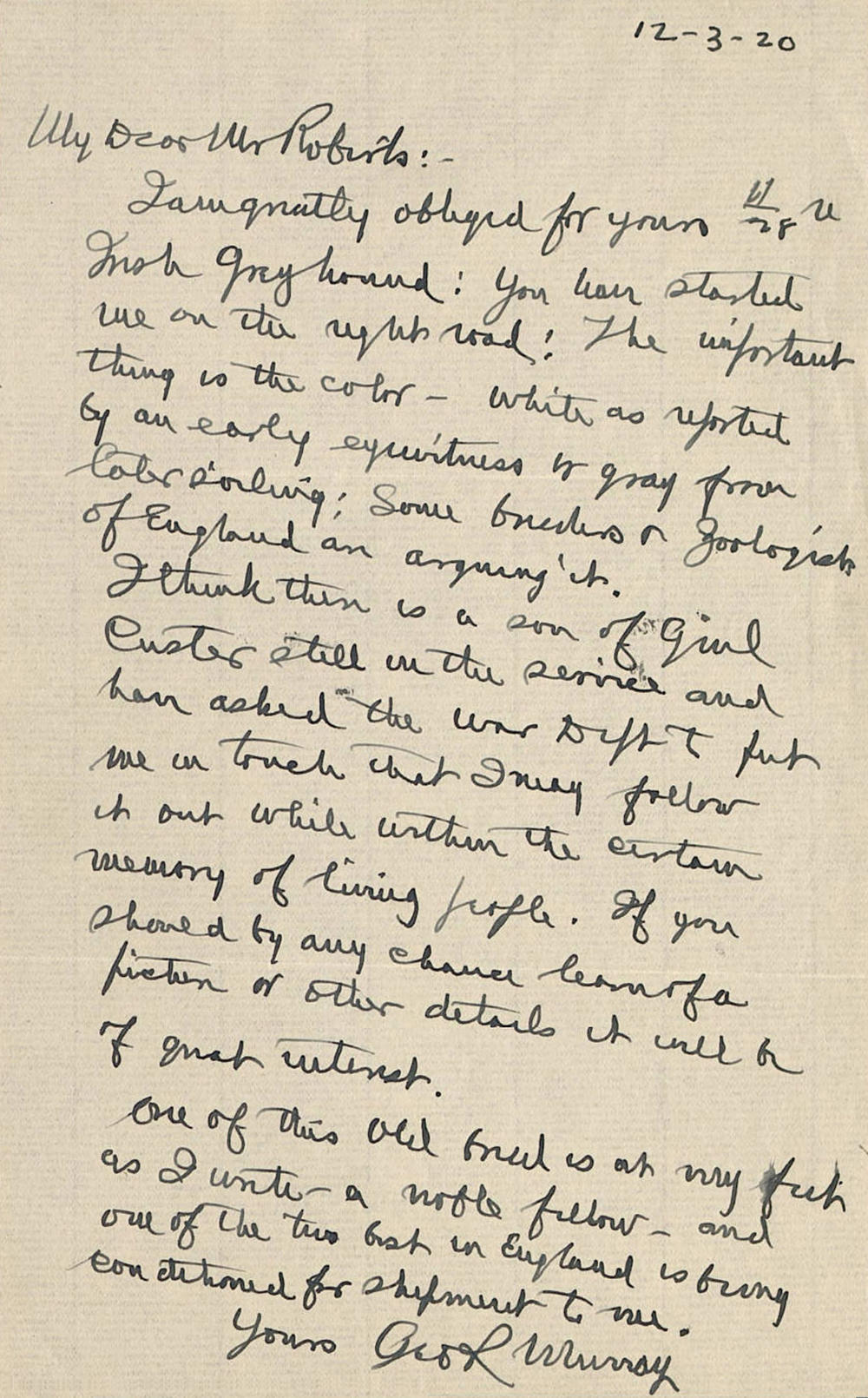

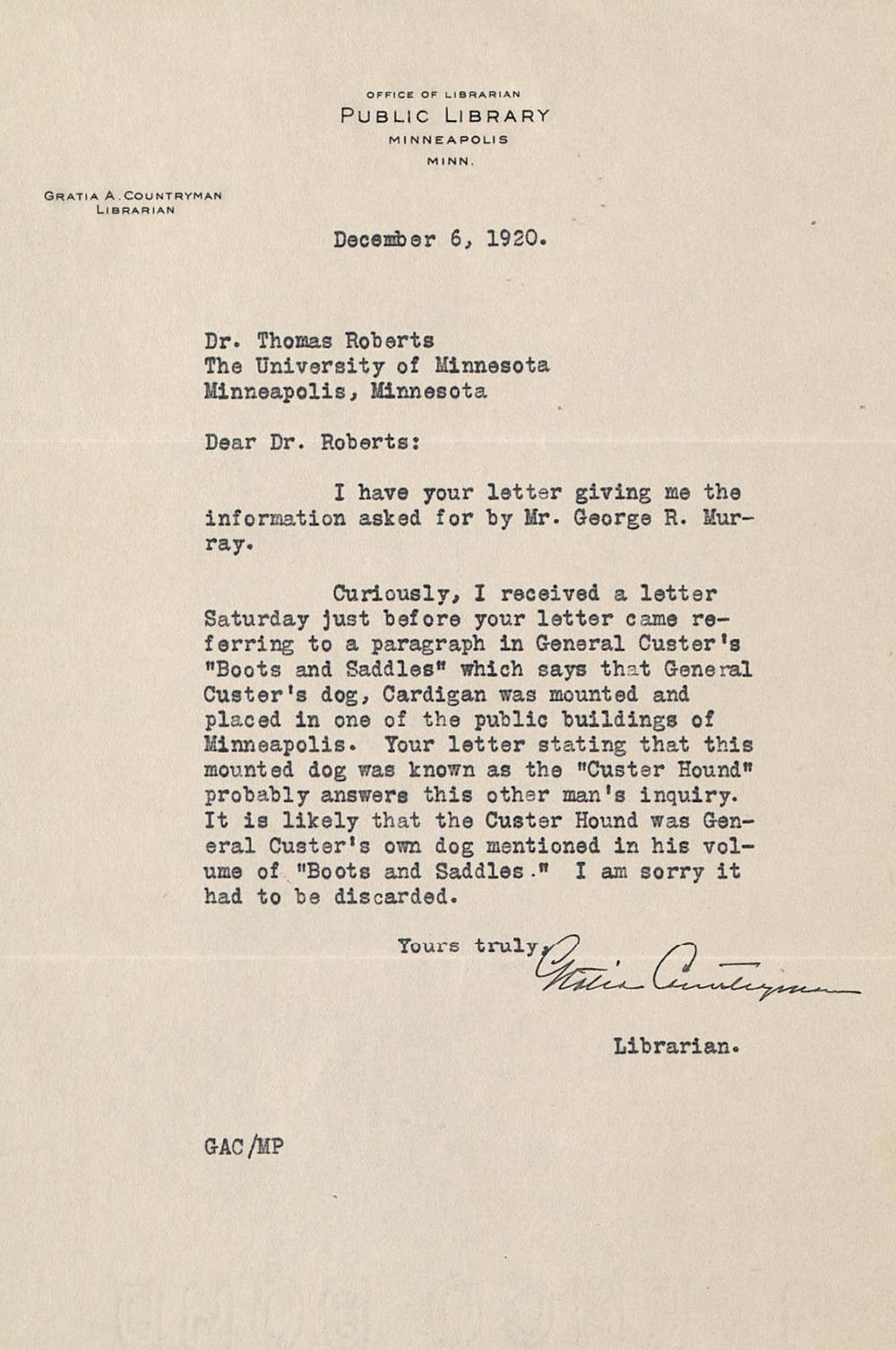

Roberts informed Countryman of his reply to Murray and in her response, Countryman mentioned that:

“Curiously, I received a letter Saturday just before your letter came referring to a paragraph in General Custer’s ‘Boots and Saddles’ which says that General Custer’s dog, Cardigan was mounted and placed in one of the public buildings of Minneapolis. Your letter stating that this mounted dog was known as the ‘Custer Hound’ probably answers this other man’s inquiry. It is likely that the Custer Hound was General Custer’s own dog mentioned in his volume of ‘Boots and Saddles.’ I am sorry it had to be discarded.”

Murray's December 3, 1920 response to Roberts (link to text)

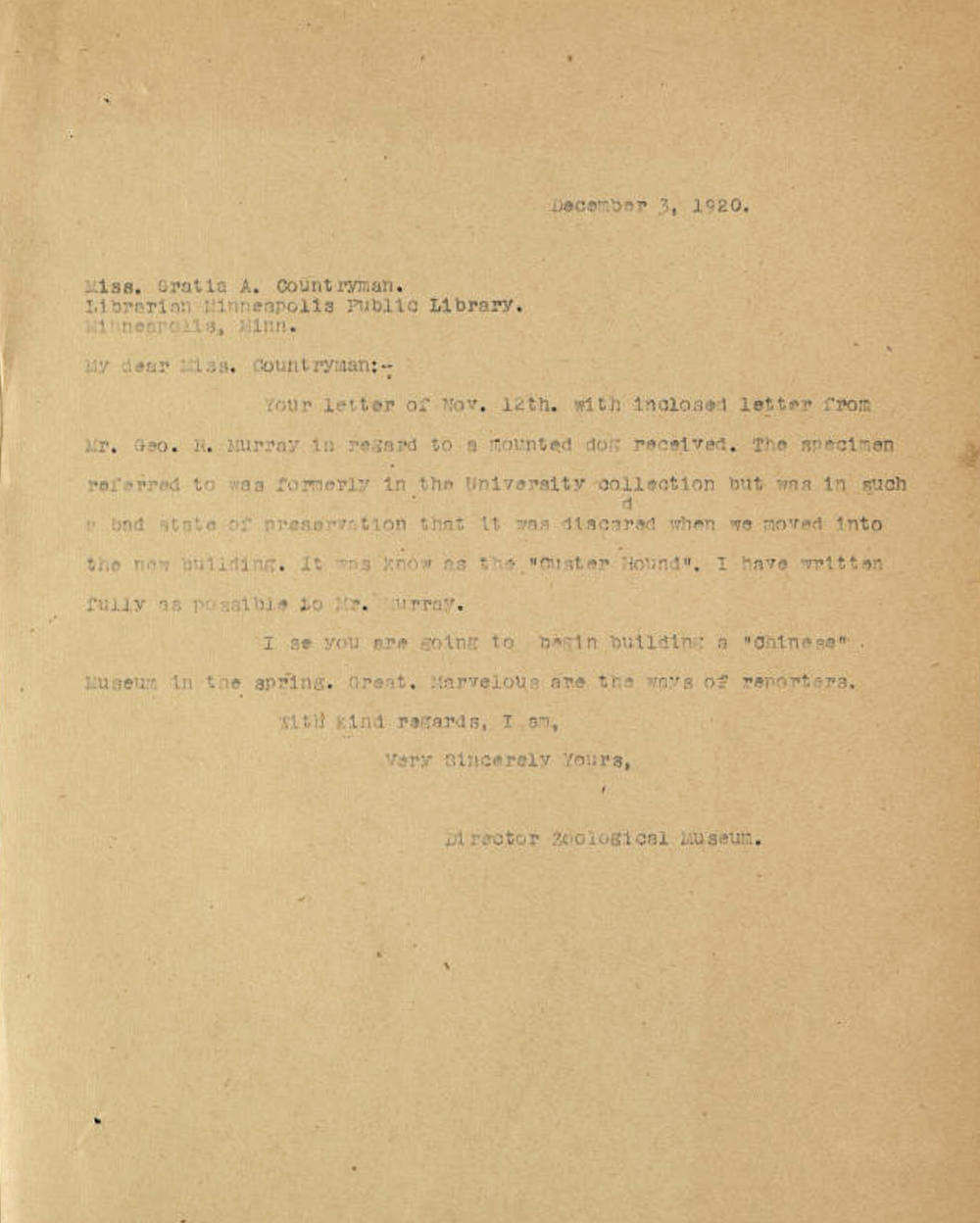

Roberts' December 3, 1920 letter to Countryman (link to text)

Countryman's December 6, 1920 letter to Roberts

If two requests following so close upon one another caused Roberts any foreboding about his decision to dispose of Cardigan, it would prove well founded. Only three years later, the Tribune articles again brought Cardigan’s fate to the fore and since then public interest never died. Over a century later, and decades after Roberts’ death, Bell Museum staff still receive inquiries concerning Cardigan’s whereabouts.

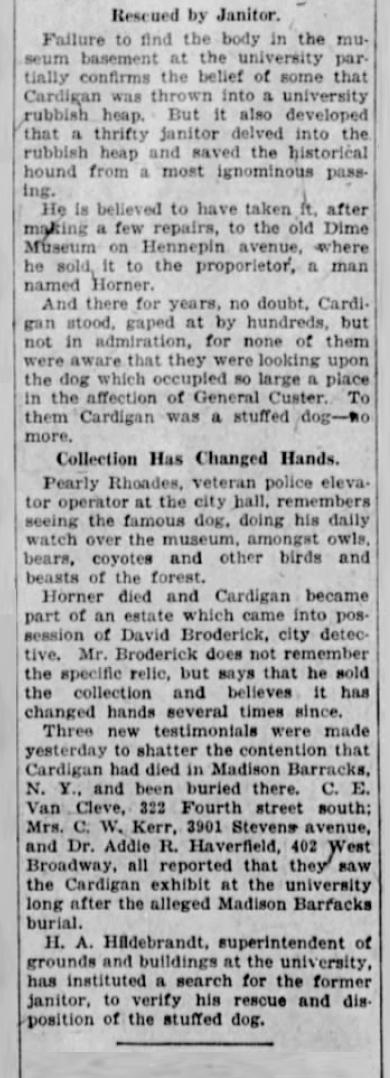

Besides confirming Cardigan’s tenure in the museum and his 1917 disposal, Rebecca Toov’s trove of archive documents also dispel most of the rumors generated by the 1923 Tribune articles, rumors reminiscent of those that swirled around Custer’s battlefield dogs a half century earlier. Cardigan obviously did not receive a New York military funeral but a posthumous deployment as an exhibit in the university’s general museum. The Tribune articles also suggested Cardigan’s mount outlived its disposal, being rescued from the trash heap only to be lost again.

Archive files show that items disposed in Cardigan’s trash heap included moose and bears, albino deer, porcupines, badgers, eagles, pelicans, and even a sacred white buffalo. The only reason a thrifty custodian might salvage a mounted dog from amidst such exotic company is if it was specifically being saved due to a historic connection with Custer. Yet the next day, the story relates the custodian sold Cardigan to a dime museum without anyone being aware of the dog’s identity. The narrative is woefully inconsistent in that Cardigan’s mount was saved because of its great historic value yet subsequently sold without appraising the buyer of the very thing that might assure a high price. While already lacking credibility, the tale then veered into the absurd.

“And there for years, no doubt, Cardigan stood, gaped at by hundreds, … but not in admiration, for none of them were aware that they were looking upon the dog which occupied so large a place in the affection of General Custer. To them Cardigan was a stuffed dog – no more. …”

“… Horner [owner of old Dime Museum on Hennepin Avenue] died and Cardigan became part of an estate which came into possession of David Broderick, city detective. Mr. Broderick does not remember the specific relic, but says that he sold the collection and believes it has changed hands several times since.”

Minneapolis Tribune Sunday, March 25, 1923

The tenor of the writing suggests Cardigan’s mount had been lost in the mists of time. Yet, the Tribune articles were published only six years after Cardigan’s disposal. With a week of front-page newspaper coverage on the Cardigan search, any stuffed dog bigger than a beagle might have been brought forth to claim Cardigan’s title. The complete lack of any candidates suggests a remarkable scarcity of large, mounted dogs in 1923 Minneapolis.

A Dime Museum did exist on Hennepin Avenue from 1896 to 1890 before it moved to the corner of Washington Avenue and First Avenue South and changed its name to the Palace Museum. In 1897 William Horner leased the museum and Jessie Queen worked as an actress there. By 1900, Mrs. Jessie Horner, widow, was the museum’s proprietor and David C. Broderick acted as museum manager. The two married the following year but beginning in 1904 the museum had a string of new owners before it finally closed its doors in 1906 – over a decade before Cardigan was tossed out of the Zoology Museum with a cadre of other mounts.

While I admit that Cardigan continuing as a dime museum display is a more plausible tale than that he once fought the combined military might of the Lakota and Cheyenne nations to a draw on the Greasy Grass battlefield, with the addition of the archive information it is difficult to overstate how unlikely either story is.

There is little doubt that Cardigan’s mount was disposed of in early 1917 and did not embark on a final tour of Minneapolis’ curio shops. Yet Toov’s documents show that Cardigan’s tale still had one legitimate twist. Nearly all sources say that Cassius Terry was Cardigan’s last owner and the one who had him preserved after death. Yet, the General Museum registrar shows it was another Minneapolis minister, Edwin Sydney Williams, who donated Cardigan’s mount to the museum.