There is no question that in the past, our department collected and held materials it should never have. In the Geological and Natural History Survey’s Eighth Annual Report for the year 1879, Winchell noted:

Ever since the beginning of the geological survey a class of specimens has been increasing for which no provision has been made. They consist of ancient stone hammers, arrowheads, Indian pottery, and other relics of the Mound Builders and the Indians. It is designed to prepare a suitable place of deposit for these specimens, so that they may be on exhibition, and so that they may serve as a nucleus for the gathering of a full series of these interesting relics. … The General Museum of the University, being established by State law, is the proper place of deposit and exhibition of such articles.

The following year, Winchell added the first ‘Catalogue of Archaeological Specimens in the General Museum’ to the Survey’s Ninth Annual Report for the year 1880. Of the 57 numbered entries, 28 included funerary items or skeletal remains taken from burial mounds near Big Stone Lake, Lanesboro, Rutland, Green Lake, and St. Peter. The remainder ranged from pottery to pipes, copper or stone tools, along with the Chippewa bark canoe Winchell used in his survey work (which is now stored at the Science Museum of Minnesota).

Catalogues of Archaeological Samples in the General Museum

The Donors of the General Museum's 'Archaeological' Collection

Some of the funerary goods and skeletal remains stolen from burial mounds were donated by citizens and amateur archaeologists, but a dozen of the 28 burial mound entries were collected by Winchell, Charles Hall, and Warren Upham - all University and Survey staff. That list will be added as an appendix, but I can confirm that one of the three human skulls collected from the burial mounds at Big Stone Lake (listed as Item 12 in Winchell’s catalog) remained in the department’s collection until fall of 1997 as I came across it when moving into a Pillsbury Hall office that summer.

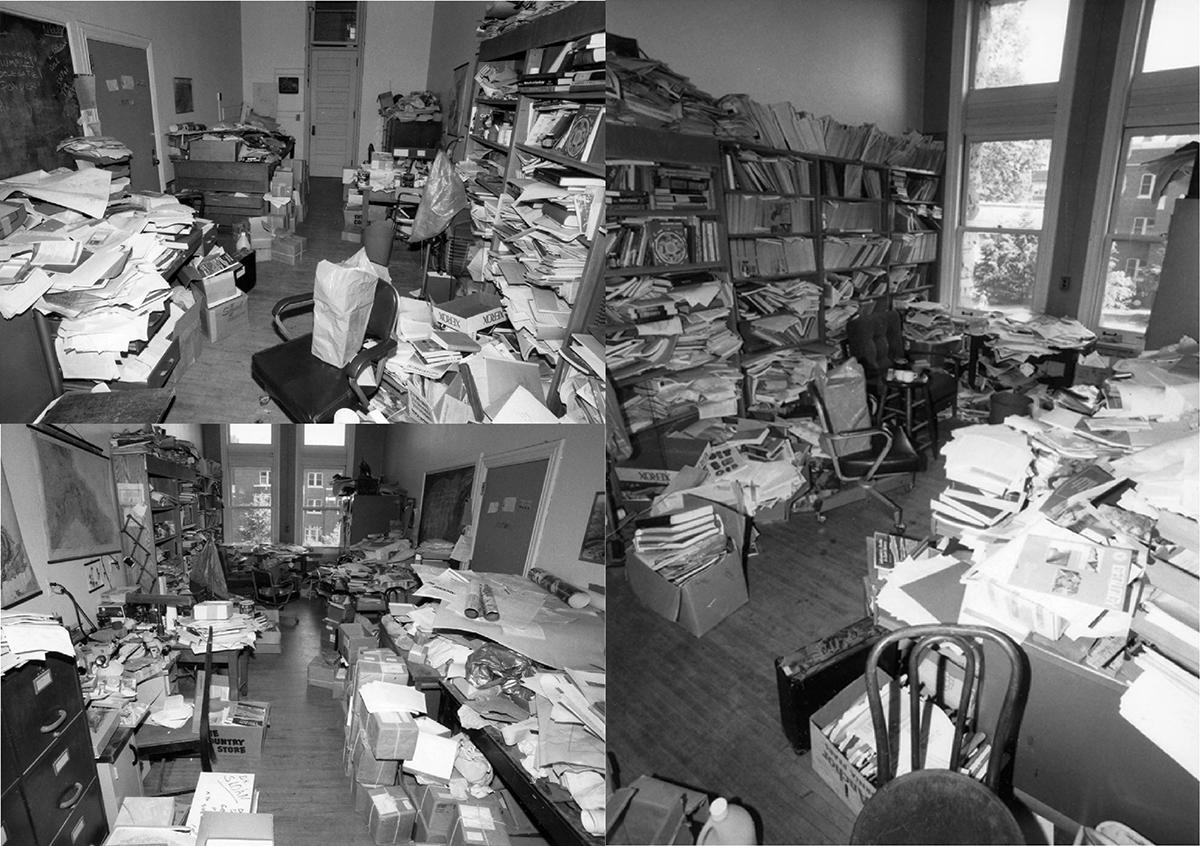

Pillsbury 103 in May of 1987 (photos courtesy of UMN photographer Patrick O'Leary)

In the decade between when these images were taken and my moving into the office, the office's contents had dramatically increased - to the point that no one had made it to the windows in years.

Skeletal Remains

Robert (Bob) Sloan retired from the University of Minnesota in spring of 1997. His office (Pillsbury 103) supposedly had only been used by three faculty members since Pillsbury Hall was built in 1889 and all three were paleontology packrats. At the time Sloan was leaving, most of his office was filled waist- to chest-deep with books, correspondence, stacks of materials, and boxes of fossils - almost all of which were left behind. While I was helping Sloan gather the few things he wished to take, he mentioned that somewhere in the office there were Indian skeletal remains that had been used as teaching aids in past paleontology classes. Sloan said those remains were supposedly taken from a burial scaffold near the location of the Battle of Pezi Sla (Greasy Grass, also known as Little Bighorn) by an early department paleontologist. I spent the summer of 1997 sorting and clearing the office, but my initial goal was to discover if skeletal remains still existed. It was not a simple task; the office was over 30’ in length and 12’ wide, with nearly all the floor space holding stacks of materials one to two meters high. The search uncovered historic 1880s and 1890s journals, type specimens of fossils, and early museum records that were hidden amid literally tons of materials. I finally found one box with a human skull and bones. But to make things worse, the other bones clearly showed the remains came from more than one individual. Additional boxes followed and by the time the room was completely searched, I thought I had partial remains from at least three and possibly four individuals. Regrettably, my estimate proved to be naïve.

In 1997, the Anthropology department was nearing the end of a multi-year rematriation program to return the Indigenous skeletal remains they held in accordance with state and federal law. A 1999 National Park Service Inventory of Native American Human Remains in the Possession of the Minnesota Indian Affairs Council[1] lists skeletal remains from 1059 individuals, of which 757 (nearly 72%) came from the University of Minnesota. In fall of 1997, I arranged with Anthropology staff to have the skeletal remains from Pillsbury included in their rematriation program. One anthropology graduate student later told me the remains we held most likely came from seven individuals. At the time, I thought the number was too high, but later learned that Winchell reported multiple remains coming from Minnesota, beyond Sloan’s oral communication of some Montana remains. Hence, the anthropology program’s estimate was likely correct. The first skull I encountered had a peeling painted number 12, confirming it was one of three skulls taken by Winchell from a mound near Big Stone Lake included in his 1880 list of archaeological materials in the museum collection.

The 1999 Park Service inventory linked below also includes a somewhat cryptic reference:

At an unknown date, human remains representing 13 individuals were most likely removed from site 21-PO-3, the Pelican Lake Gravel Pit site, Pope County, MN by unknown person(s) and donated to the University of Minnesota Geology Laboratory. No known individuals were identified.

No associated funerary objects are present.

1999 National Park Service Inventory of Human Remains

I am unsure how to interpret this reference. It may be a mistaken acknowledgement of the human remains rematriated in the autumn of 1997, but the number differs from what was reported to me at the time. We also returned the remains with the information that they came from different localities including one possible Montana site. To my knowledge, there was never an entity known as a Geology Laboratory, although the College of Liberal Arts occasionally used that term to refer to our introductory lab program. If these were the remains rematriated in 1997, the given location is definitely incorrect for some, if not all, of the remains. Alternately, it is possible that the remains of 13 individuals from Pelican Lake were given to our department and transferred to the Anthropology department long before I arrived in 1994. However, Sloan never mentioned such a donation and he believed the only human remains we held had been acquired early in the department’s history.

Whether the 13 individuals listed in the 1999 Federal Report were a separate group or the misidentified remnants of the museum’s original holdings, five Winchell reports (1880, 1881, 1882, 1884, and 1885) listing archaeological specimens in the General Museum attest that at one point the remains of fourteen or more individuals were held by the department. In addition, many funerary objects were also held. Du Anne Heeren and I have gone through every cabinet currently in the department’s general collections and were unable to find any of these materials. Apart from the human remains rematriated in 1997, I suspect the materials were lost or transferred to another department or institution although I have yet to find any documentation of their current location or past fate. However, I can confirm that all human remains held by our department since 1994 were rematriated. That they were ever part of our collections is more than regrettable, it was wrong. Their presence in our department served no noteworthy purpose, and since 1976 their collection would be considered a felony under Minnesota law. That it took over two decades beyond 1976 to rematriate them is more than problematic.

[1] Federal Register Vol. 64, No. 152 Monday, August 9, 1999 - Notices 43211, Department of the Interior National Park Service Notice of Inventory Completion for Native American Human Remains and Associated Funerary Objects from the State of Minnesota in the Possession of the Minnesota Indian Affairs Council, Bemidji, MN

Other Materials

If the above were not bad enough, from 1881 to 1927, our museum held an oak beam alleged to be one of four gallows beams from the scaffold used to murder 38 Dakota men at Mankato on Dec. 26, 1862. The Nov. 24, 1881, issue of the Ariel (a monthly forerunner to the Minnesota Daily) announced its arrival at the museum, quoting its donor’s (John Ford Meaghan) letter to Professor Charles Hall. While most references to the article cull the second sentence to avoid offence, I think it is important to acknowledge the extent of the article’s racism as it reflects the prevailing attitudes at the time our museum collection was forming.

"Agreeable to promise I have sent the last stick of the 'Indian Gallows' this p. m. to the St . Paul & Sioux City depot to be forwarded to the University of Minnesota. It is rather a hard looking 'relic' and you may be disappointed when you see it, but I can assure you it did the business and completely civilized ten Sioux Indians…” - J. F. Meaghan

The full article is linked below, but the equivalence of murder and ‘civilized’ is a visceral reminder of the intense prejudice prevalent two decades after the US-Dakota War. While there is considerable controversy whether the beam was actually part of the scaffold, that belief accounted for its presence in our museum. Even if the beam identify was false, our department displayed it as a relic of the Mankato hangings and considered that display justifiable. In 1927, the University wanted to dispose of the then-decaying beam and donated it to the Blue Earth County Historical Society where it remains in storage.

Ariel Article on Mankato Beam

And while a loom, cloth, and tools of African origin mentioned in the museum lists might be considered acceptable displays, the two braids of hair taken from a native of the Hebrides were not. Nor was the lock of braided hair from an Indigenous man known in the museum registrar as ‘Dirt-in-the Face’. It is exceedingly difficult to envision these materials being donated with ‘informed consent’. The hair was more likely taken and displayed because these individuals were considered to be not as fully human as the Euro-American donors. Other items, like a sample of tattooed skin taken from a cadaver, may initially simply seem bizarre, but reflect deeper biases. In the 1880s, tattooing was relatively uncommon. Tattoos were most common among Indigenous people and sailors; the latter considered to be of such low social status among Euro-Americans that official records seldom noted their deaths.[1] It is unlikely that the deceased agreed to this mutilation of their body or the display of their skin. More plausibly, a doctor assumed they had the right to take skin from a less privileged individual and donate it to the museum. And unfortunately, the museum’s acceptance only confirmed that donor’s assumption.

Again, Du Anne Heeren and I have searched all the cabinets of the department’s general collections looking for these materials. And while we found many things that should not have been a part of the collection, such as radioactive samples, carcinogenic oils, and even nude photos from the 1960s, none of the so-called ‘archaeological’ samples of Winchell’s museum lists remain in the department holdings.

[1] Tattooing did become more common during the Civil War as a way for soldiers to identify their bodies in case of death; at a time before dog tags became standard military issue.