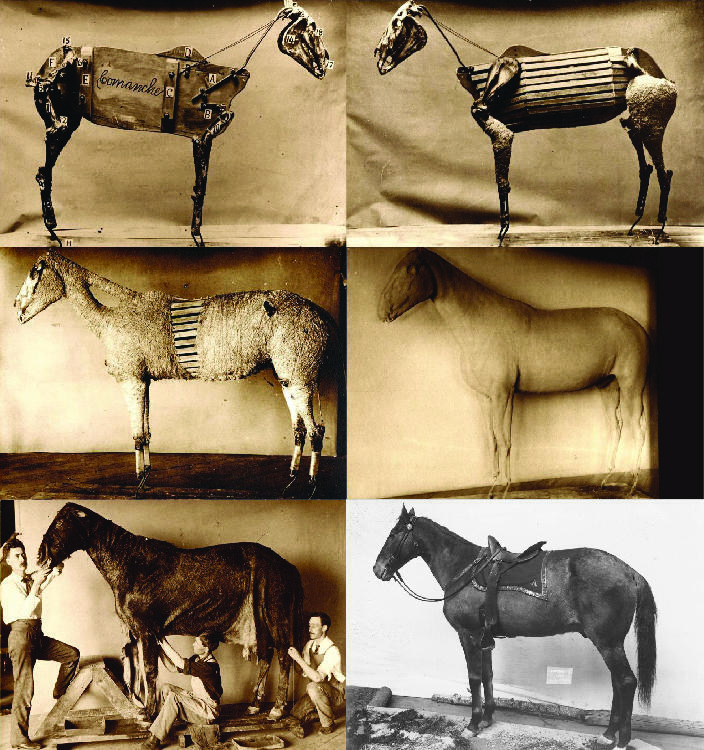

The presence of Cardigan’s skull in the museum collection is somewhat surprising, as museum mounts at the time often incorporated skulls and other skeletal elements. When Comanche, a survivor of the Greasy Grass battle, died on November 7, 1891, at age twenty-nine, his skin was mounted on a frame of wood and bone to be displayed in the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History.

However, the General Museum registrar is clear that Cardigan’s skull was a separate donation to the museum from Edwin Sydney Williams. The registrar lists the skull’s arrival as 1880, rather than 1879, which suggests Cardigan may have died in late 1879, as the donations (or their recording in the registrar) straddled the new year. And while even the best mount can decay within decades, bone is more resistant so Cardigan’s skull may still survive. The General Museum registrar was not the only source to place Cardigan’s skull in the Bell Museum collections. Another report from the university archives claims it was there as recently as the 1960s.

Images showing the process of creating the mount of Comanche. Note that the horse's skull and limb bones were including in the mount.

On January 2, 1992, Stephen Youngkin, a Scottish Deerhound devotee and historian, wrote to Penelope Krosch, head archivist at the University of Minnesota, inquiring about Cardigan. In her January 21 reply, Krosch confirmed Cardigan had initially been given to the Terrys and that Cardigan’s mount was probably discarded when the collections moved into a new building in 1916. However, Krosch went on to relate that:

“The skull was still in the Bell Museum of Natural History collections until the 1960s because a friend of mine saw it there. At the time he thought it should be sent to the museum at the Little Big Horn Battleground. Unfortunately, he did not pursue the matter and a later Curator of Mammals may have disposed of it. The current curator, Dr. Elmer Birney, will check the few dog skulls in the collection when time allows. My friend remembers that the skull was marked in ink on the underside as belonging to Custer's dog.”

Youngkin's letter to Minnesota Historical Society - November 4, 1991

Youngkin's letter to Krosch at University Archives - January 2, 1992

Krosch's response to Youngkin - January 21, 1992

No copy of this correspondence remained in the university’s archives, but Stephen Youngkin was kind enough to contribute it to Brian Duggan when Duggan was drafting his book on the Custers’ dogs. Duggan paid the favor forward, sending copies of the letters back to our archives.

Sharon Jansa, the Bell Museum’s current curator of mammals, scoured their mammal collection and reports that Cardigan’s skull is no longer in their curated collection. However, hope springs eternal, so there is a slight chance that Cardigan’s skull may yet be found in one of innumerable boxes of non-curated materials that the Bell Museum, like any natural history museum, accumulated over time. Or the descendants of whomever took Cardigan’s skull from the museum may one day return it. If the skull were labeled as Krosch reported, it is unlikely any curator would have disposed of it as the prestige of holding the Custers’ last known dog would have precluded that loss.

Cardigan’s Epilogue

With the addition of the university archive documents gathered by Toov, Cardigan’s story becomes a bit more complicated. Armstrong and Libbie Custer did own scores of dogs including a wolfhound they called Cardigan. And after the general’s death, Libbie placed Cardigan in the care of a St. Paul minister and his wife, Cassius Marcellus and Emily Hitchcock Terry, who were both talented scientists. The Terrys adopted Cardigan in 1876 and the photograph of Cassius and Cardigan may have been taken that year or sometime up to 1878 (rather than the early 1880s as previously thought). However, Cardigan then moved to the home of another minister, Edwin Sydney Williams, where he died in 1879. Upon Cardigan’s death, Williams had Cardigan’s pelt mounted and donated to the University of Minnesota’s General Museum along with Cardigan’s skull. Cardigan’s remains moved with the General Museum from Old Main to Pillsbury Hall in 1889. In 1916, the biological and botanical collections of the General Museum moved to new quarters in a recently built Zoology building. However, at that point, Cardigan’s mount was one of sixty-nine specimens tossed out in early 1917 because they were pest-ridden and posed a threat to other museum collections. Despite many rumors, there is no credible evidence of Cardigan’s body rising from the trash heap to begin a posthumous tour of Minneapolis’ dime museums and thrift stores. However, his skull remained with the biology collection as it evolved into the Bell Museum of Natural History on the Minneapolis campus of the University of Minnesota. The skull was still present in those collections at least until the 1960s. Since that time though, its whereabouts are unknown. It was either taken from the museum’s collection or lost among the museum’s non-curated materials. One day it might still be recovered.

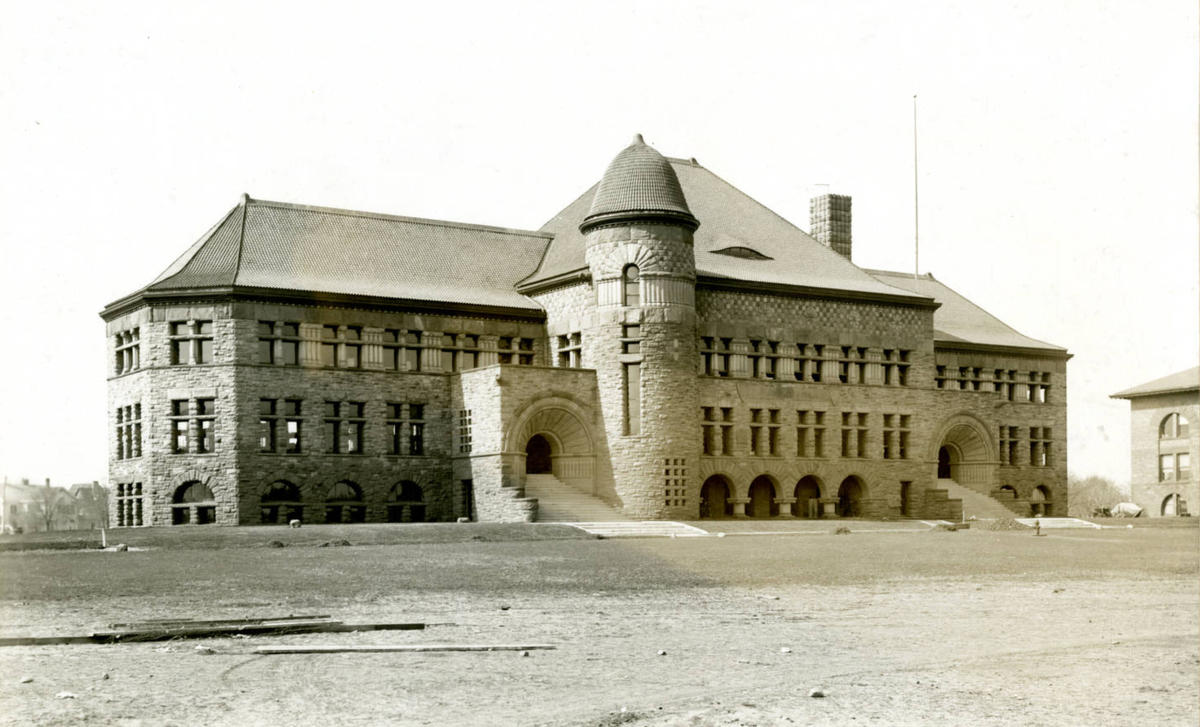

Old Main in 1878 - home of General Museum from 1874 to 1889

Pillsbury Hall in 1890 - home of General Museum beginning in 1889. Museum split into geological and zoological collections in 1916.

Zoology Building in 1915 - home of zoology collection beginning in 1916. Cardigan's mount was discarded from collection in 1917.

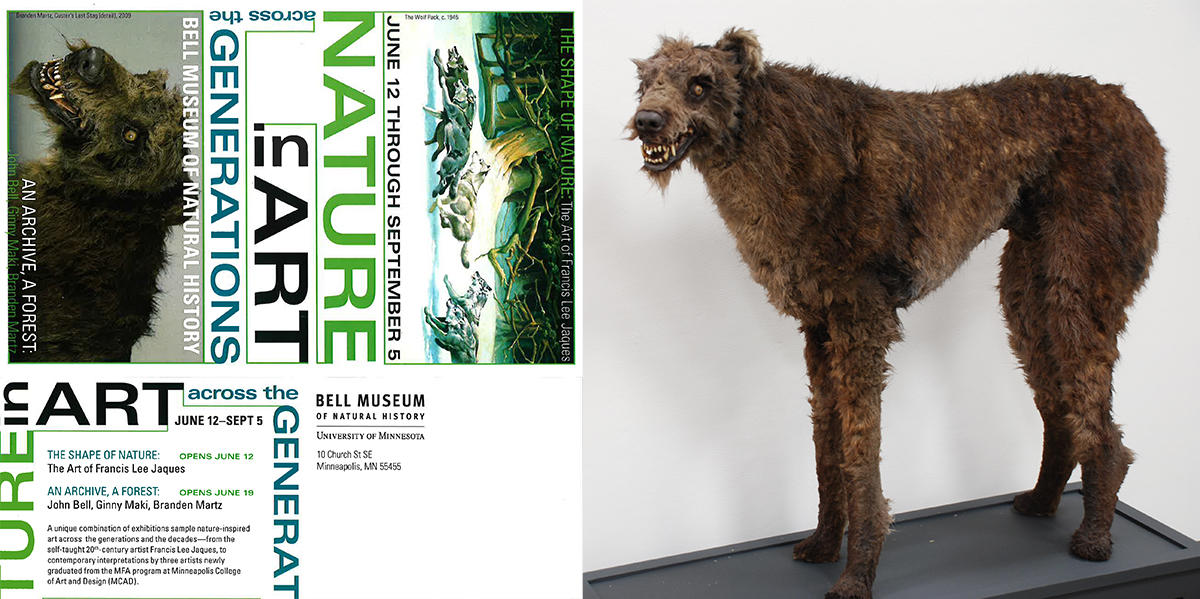

Branden Martz sculpture of Cardigan and ticket for 2009 Bell Museum Exhibit

A Final Legacy?

Yet, Cardigan might have left another legacy, as at least two people in the 1923 Tribune series claimed to have raised his progeny.

“Walter A. Eggleston, vice president of the David C. Bell Investment company, also insisted that Cardigan died in Minneapolis. He owned a son of the dog, Lord Cardigan Jr., and there was also another of the pack here, he said. Fred D. Brown, who once lived on the South Side, was also known to have owned one of the dog’s descendants, it developed last night.”

Although the series has credibility issues, on this aspect I willingly withhold skepticism as per the closing lines of Duggan’s book:

If the skull of Libbie’s Cardigan is truly lost, there can be some satisfaction in knowing his remote descendants may still be going for walks in the neighborhoods of the Twin Cities.”

- General Custer, Libbie Custer and Their Dogs – p. 288

Now that is a thought that makes every encounter with a large staghound mix more magical.

Any comments, concerns, or suggestions?

email: Kent Kirkby ([email protected])

Main Sources:

University of Minnesota Archives – records gathered by Rebecca Toov

Youngkin and Krosch 1991 to 1992 letters concerning Cardigan (forward by Brian Patrick Duggan)

General Custer, Libbie Custer and Their Dogs, by Brian Patrick Duggan (link to book at Amazon.com)

A Painted Herbarium – The Life and Art of Emily Hitchcock Terry (1828-1921) by Beatrice Scheer Smith (link to book at Amazon.com)

Boots and Saddles or, Life in Dakota with General Custer by Elizabeth Bacon Custer

Congregational Work of Minnesota (1932-1920), compiled and edited by Warren Upham

Minnesota Newspaper articles from Minneapolis Tribune, Minneapolis Star, Saint Paul Daily Globe, Freeborn County Standard, and The Austin Daily.

United States Census records from 1850 to 1880

Saint Paul and Minneapolis City Directories 1872 to 1884