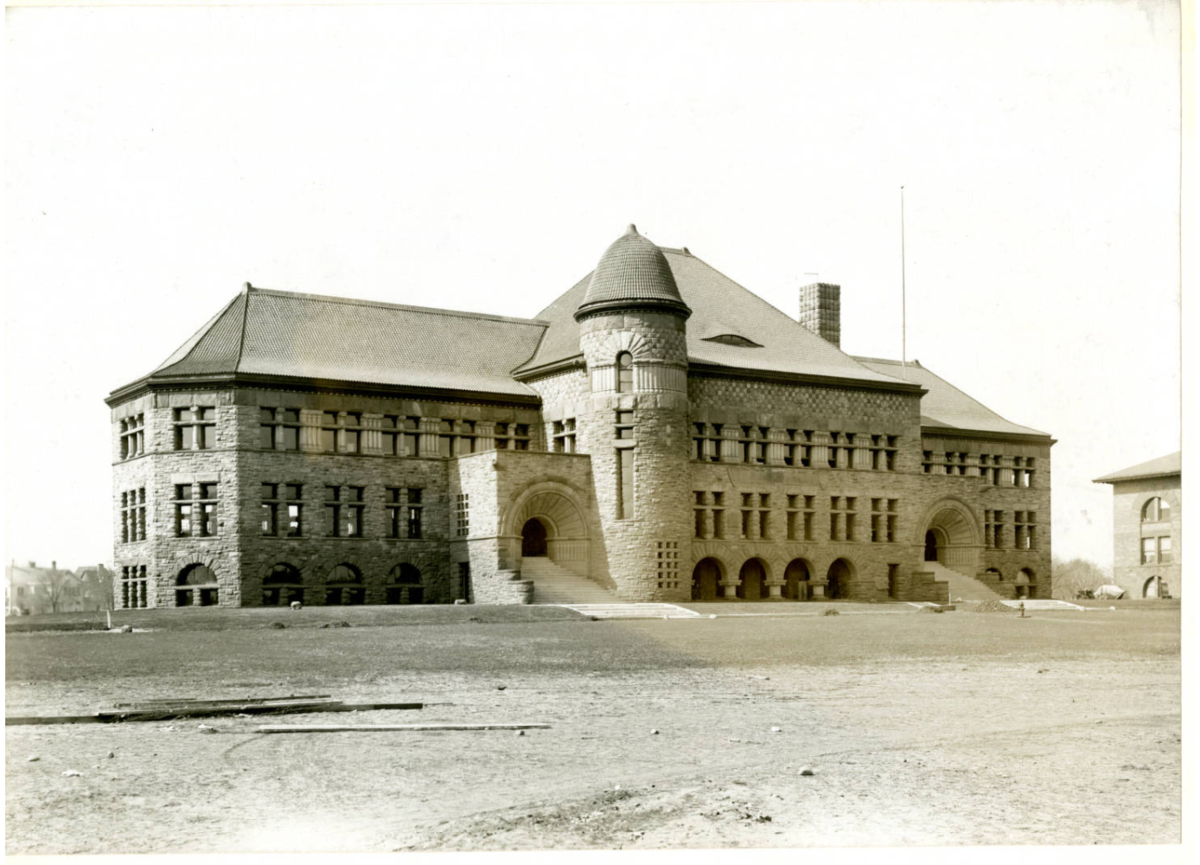

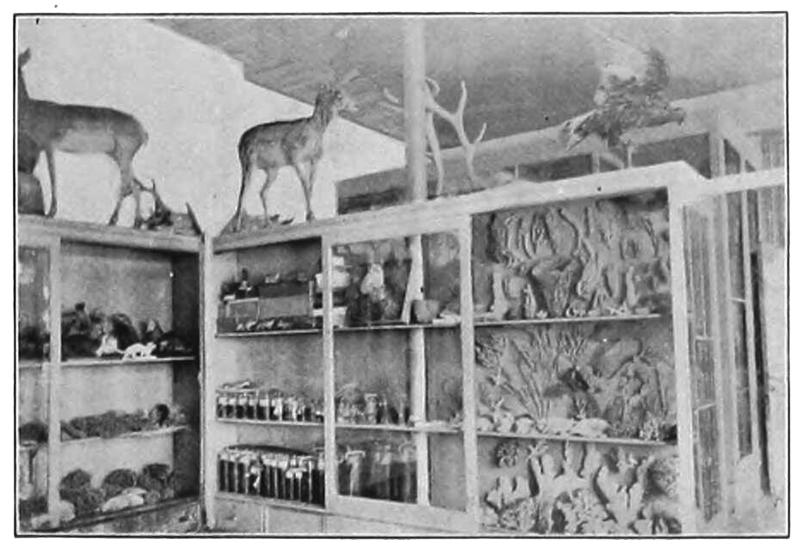

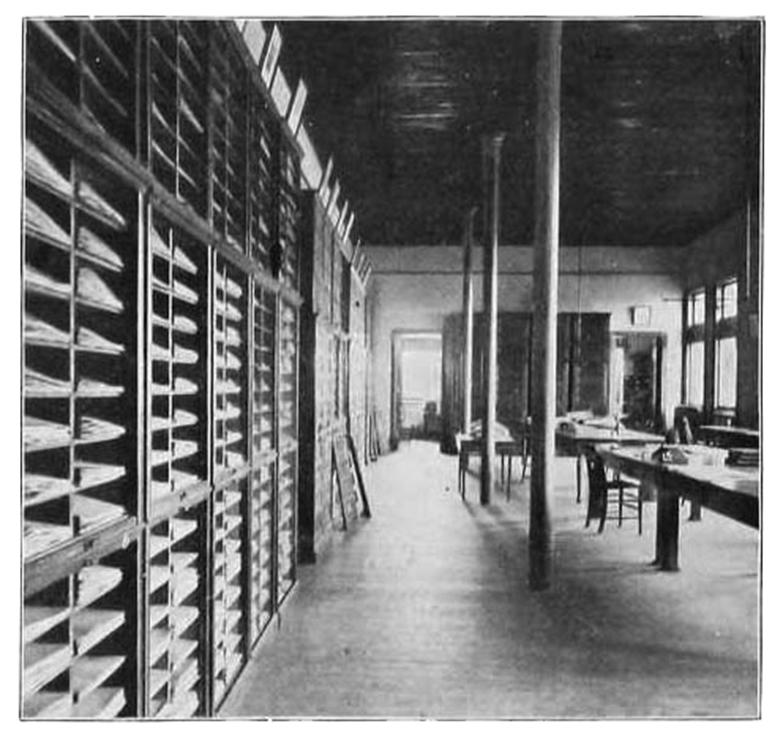

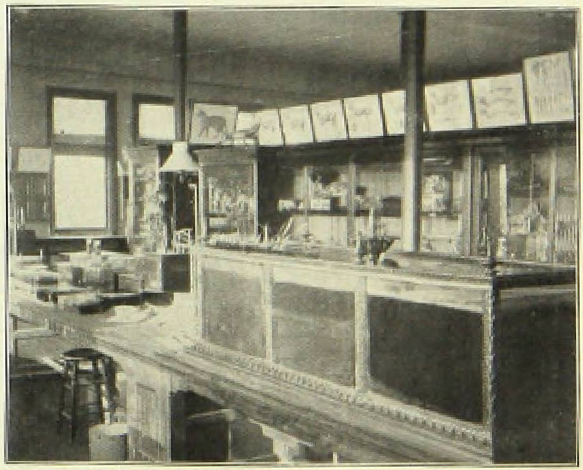

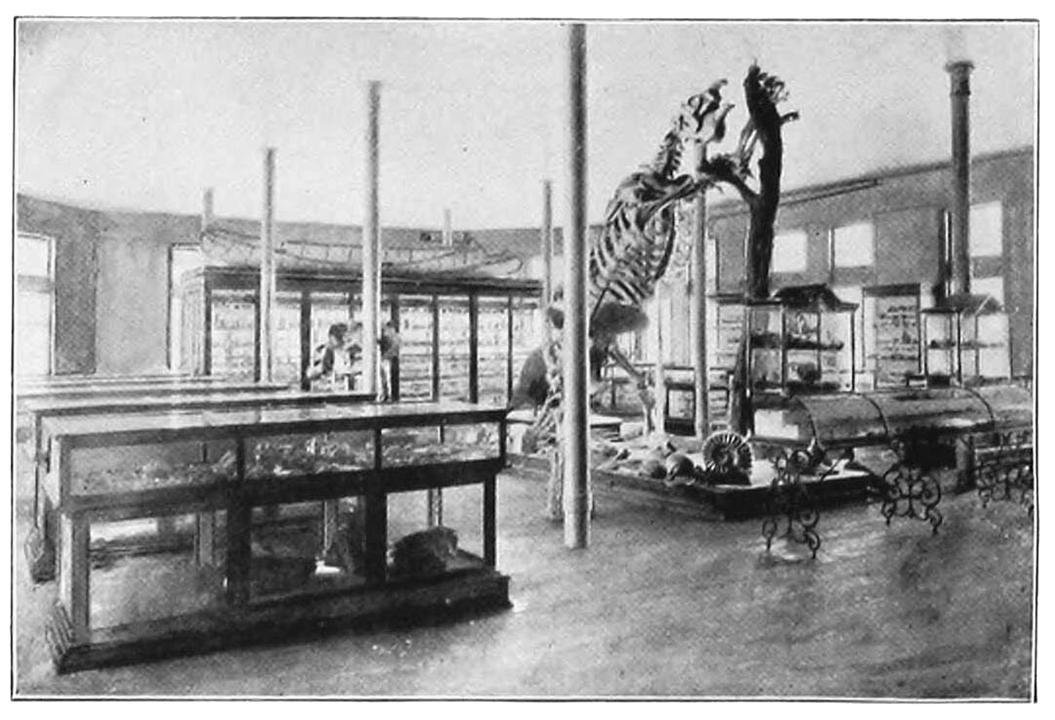

Geology Museum in Pillsbury Hall (from 1897 Gopher Yearbook)

Earth and Environmental Sciences may be the only University of Minnesota department that essentially began as a collection. In his inaugural speech as the first University of Minnesota President on Dec. 22, 1869, William Watts Folwell listed the three most important contributions the University could provide the state. The first was a great Normal School for teachers, the second a great library, and the third was the development of a great museum of history, natural history, and art. While Folwell added art and engineering to his museum vision, he emphasized the importance of having a geology collection.

“The museum is the perfection and climax of object-teaching . One glance at a fossil skeleton, the sight of a piece of coral, a trilobite, or a fern from the coalbeds gives to the young geologist an insight not to be won from volumes of reading.”

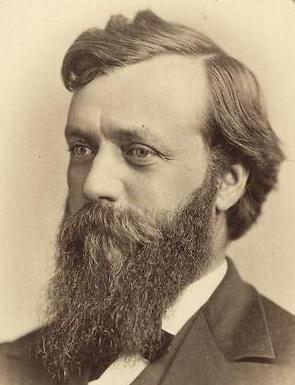

In 1872, the appointment of Newton Horace Winchell comprised the University’s first significant step towards the development of Folwell’s envisioned museum. Newton was not Folwell’s first choice to develop his museum. Folwell originally hoped to lure Alexander Winchell, a well-known University of Michigan professor and the State Geologist of Michigan for the post. However, at the time of Folwell’s inauguration, the University of Minnesota consisted of eight faculty, 100 students, and a single building. As an institution, it fell far below Alexander Winchell’s expectations for someone of his prestige. Instead, he suggested his younger brother, Newton, for the role. Newton had taught high school before coming to Michigan to be trained as a geologist by his older brother. Hence in 1872, both brothers left Michigan; Newton to the newly established and still struggling University of Minnesota while Alexander became the Chancellor of Syracuse University. After the Panic of 1873 destabilized Syracuse, Alexander became a professor at Vanderbilt University, before finally returning to finish his career at Michigan.[1]

[1] It should be noted in passing that everyone in our department should be grateful Minnesota ended up with the younger Winchell brother. Although Newton was a product of his time, adhering to many of its discriminatory views, in 1878 Alexander wrote one of the most profoundly racist pseudo-scientific treatises of his time: ‘Adamites and Preadamites’. This work not only sought to prove the ‘scientific inferiority’ of other races but claimed separate origins for each ‘race’ of humans. Even by the standards of its time, Alexander’s treatise was notable for its racist claims, and his work is still embraced and cited by modern white supremacists.

Winchell and Early Department History

Newton Winchell was neither the first to teach geology at the University of Minnesota nor our first State Geologist. In 1864, Governor Henry Swift appointed August Hanchett as state geologist. Hanchett had little background in geology, so he hired Thomas Clark who completed a brief 82-page report of the physical geography, meteorology, and botany of the northeastern district of Minnesota before Hanchett was dismissed. The following year, Governor Steven Miller appointed Henry H. Eames in Hanchett’s place. Eames published two even shorter reports on Minnesota’s geology, but in doing so managed to both overspend his budget and spark a false gold rush near Vermilion Lake based on his highly inflated reports of gold discoveries. Although the interest in this ‘gold rush’ quickly faded as subsequent investigation revealed no commercial gold deposits, the false reports led to the Bois Forte Band of Ojibwe being forced into an 1866 treaty to relinquish their land claims on the shore of Lake Vermillion. Those claims were not reestablished even after the false gold rush faded from memory.

Having been twice burned by governor-appointed state geologists, the legislature was content to let President Folwell write the bill to establish the Geological and Natural History Survey of Minnesota and choose its first director. That law was passed by both houses and approved by Governor Horace Austin on March 1, 1872. It was then that President Folwell chose Newton Winchell to lead the new survey. In the law, Folwell included a provision for the establishment of a Museum of Natural History at the University that would be organized, setup, and maintained by the Survey. Hence, Winchell’s Minnesota tenure, the survey, our department, its museum, and our collections all originated in the same bill.

Prior to Winchell’s arrival in September of 1872, Edward H. Twining taught the university’s first courses in physical geography, mineralogy, and geology. In a tribute to both Twining’s abilities and the University’s small staff, Twining jointly held the positions of Professor of Chemistry and Instructor in Natural Sciences and French. Twining even taught geology right after Winchell came to Minnesota[1] as establishing the Survey consumed much of Winchell’s first year. Winchell’s survey work saw a brief hiatus in July and August of 1874, when Winchell served as the geologist for the 1874 Black Hills Expedition, but the museum was already in place prior to the Survey’s Fourth Annual Report for the year 1875. In that report Winchell also noted that a nucleus for the museum existed at the University prior to his work, so some of our earliest collections may have predated the department.

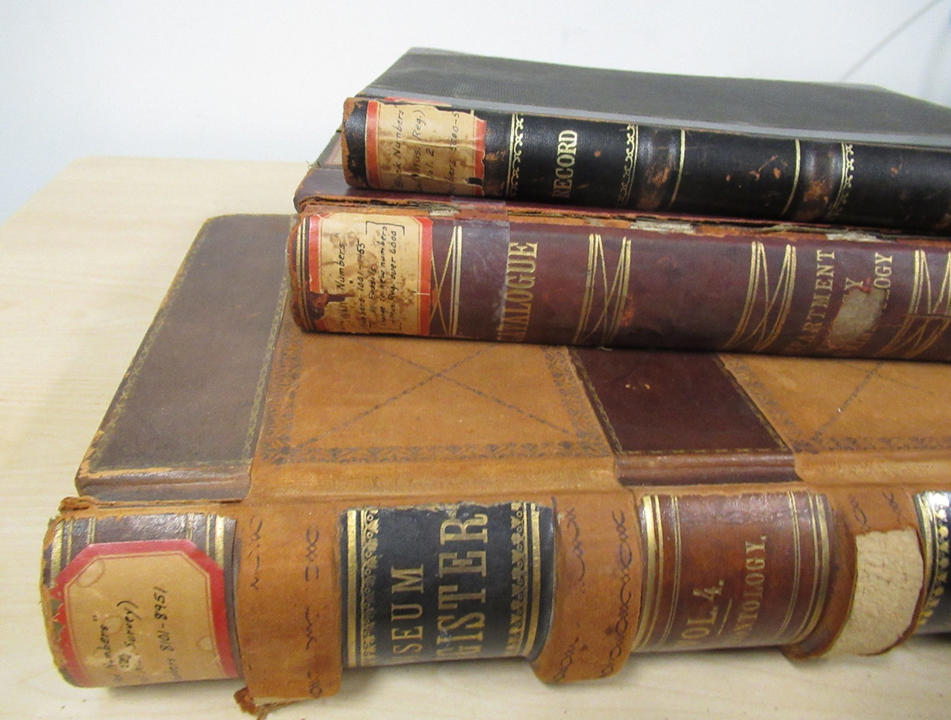

Tracing our department’s collection history is complicated by the loss and incompleteness of its known records. Atypically, the collection’s early years have the best records as there only a few individuals involved and it was relatively easy to record the collections as they began. Later, with more staff, vast amounts of material, and no clearly designated museum director, materials began to disperse or were lost. Some museum materials moved to other departments while demands for space and resources in a growing department reduced oversight and maintenance of the remaining collection. The end of the geology museum is hard to define as so much was dispersed even before its doors closed and the space was converted to offices and classrooms. However, in department correspondence with the university administration, the Geology Museum was last mentioned in the 1958-59 academic year. After the summer of 1959, our collections were simply referred to as the department collections.

The loss of material over time was tremendous - as was the misplacement and loss of collection records. The General Museum’s only surviving registrar is volume 4, which implies at least three other volumes once existed. The lone survivor was buried in a cluttered office (Pillsbury 103) along with a few other curator records. Those survived simply because they were lost for decades, an examples of ‘preservation by neglect’ – a pattern repeated all too often in our department.

[1] Twining, a Civil War captain of the 33 Illinois Volunteers, had a diverse academic career. An 1852 graduate of Wabash College and a master’s student and assistant chemistry instructor in the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale before the war, he was appointed to a professorship in Washington and Jefferson College in Pennsylvania in 1866, moved to the University of Minnesota in 1869, and was at the University of Missouri after 1872 as a professor of Latin. In 1882 he became an Engineer with the Mississippi River Commission.

Dispersal and Loss

However, the complex institutional genealogy of the collections also complicates tracing their dispersal. Although the original museum began as a geology and natural history museum, it also served as the University’s General Museum, which meant its collections were more eclectic than might be expected of a geology museum. As the University grew from a score of faculty to many scores of departments, museum materials were dispersed to other departments, other institutions, and even to private homes. Large divisions are easier to track, like the separation of the General Museum into a geology and mineralogy museum (located in what is now the western halves of Pillsbury Hall’s first and second floors) and a botany and biology collection (on Pillsbury Hall’s third floor). The University created a new Department of Botany in 1890, and in 1909 the botany and biology collections moved from Pillsbury Hall to the basement of that department and from there to a new building on the St. Paul campus. Eventually a gift from the founder of General Mills led to the opening of the James Ford Bell Museum of Natural History on Church Street in 1940. From that point on, those collections benefited from robust curation and eventually evolved into the present Bell Museum on the St. Paul campus.

In contrast, the geology department only episodically provided curation of their collections and that curation was not uniform, shifting its focus between paleontology, petrography, and mineralogy as department research interests changed. Furthermore, from its start the geology department was intimately associated with, yet distinct from, the Natural History and Geological Survey of Minnesota. Consequently, collection materials moved between the two entities. The Natural History and Geological Survey of Minnesota ended in 1900 but was revived in 1911 as the Geological Survey of Minnesota. After Winchell retired from the survey in 1900, his research interests moved from geology to archaeology and he worked for the Minnesota Historical Society. As the Geology Museum was downsized and phased out, some of its materials, including large casts and Winchell’s canoe, were given to the Science Museum of Minnesota.

Consequently, materials originally collected by Winchell are known to be in the collections of the Earth and Environmental Sciences Department, the Minnesota Geological Survey, the Bell Museum, the Science Museum of Minnesota, the University Archives, and the Minnesota Historical Society, as well as their potential dispersal to other departments, institutions, and even personal households which occurs when a collection is not properly curated and maintained – as ours were for decades.