Before we get to those later tales, let us recount what is known of Cardigan’s life with the Custers – which Duggan skillfully summarizes in his book on the Custers’ dogs.

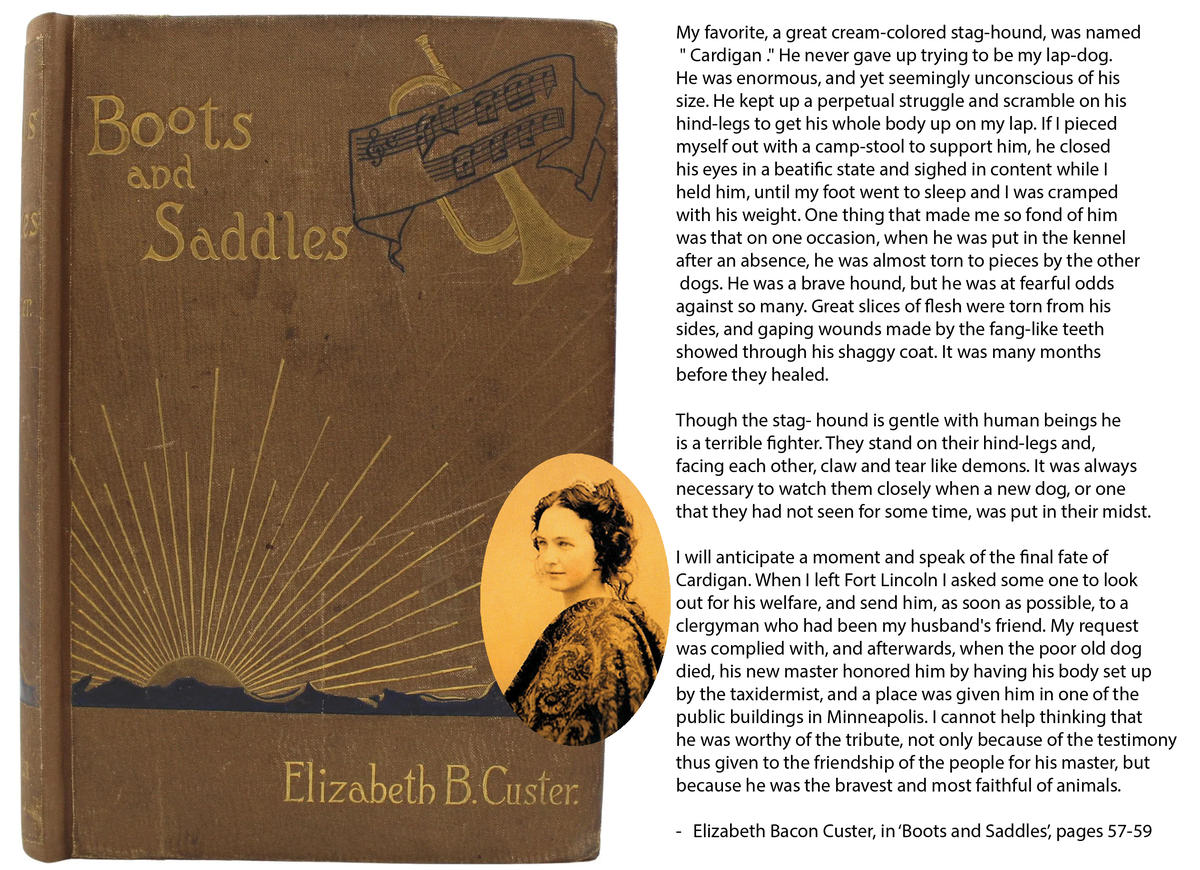

Cardigan, the namesake of Lord Cardigan of ‘The Charge of the Light Brigade’ fame, was described by Libbie Custer in her 1885 Boots and Saddles as “a great cream-colored, stag-hound.” Cardigan’s birth date is unknown but Duggan, who knows far more about dogs than I ever will, believes Cardigan must have been at least a year old to have accompanied Armstrong Custer on the 1873 Yellowstone Expedition. In his letters and articles, Custer identified four of the stag hounds on the expedition by name, including Cardigan.

Cardigan may have been one of the four staghounds who were lost at one point while chasing after an elk. On their own, the dogs traveled over two hundred miles to Stanley’s Stockade on the Yellowstone River, arriving two weeks before the expedition itself reached the site. The names of those four were not recorded, but Custer did identify Cardigan as a participant in another adventure that September. In a letter to the Turf, Field and Farm sporting magazine, Custer told how he and five of his dogs encountered a magnificent bull elk soon after riding out of camp. Custer, whose marksmanship did not always live up to his boasts, only wounded the elk with his first shot. With the dogs in pursuit, the injured elk leapt into the Mussel Shell River, seeking deep water to escape the hounds. Cardigan and his companions were undeterred, and Cardigan was one of two dogs who braved the elk’s slashing antlers to climb onto its back. When the elk tried to drown his dogs, Custer chanced a second shot into the maelstrom of struggling animals, bringing the elk down without killing any of his pack. William Pywell photographed Custer and the elk after it was brought into camp. The enormous antlers Cardigan and his compatriots had braved earlier that morning dominate the image but sadly none of the victorious pack were captured in the photograph.

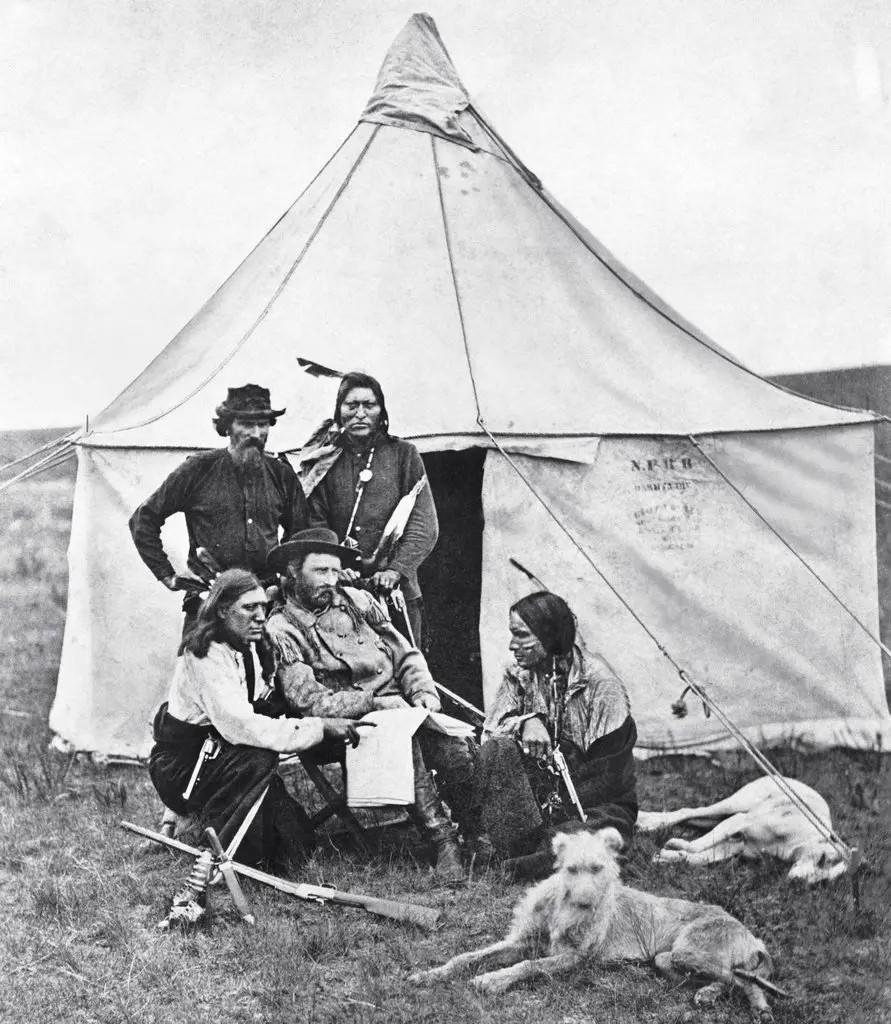

The next year Cardigan accompanied Custer on his 1874 Black Hills Expedition. This was the expedition that sparked gold rumors that led to the Black Hills being stolen from the Lakota, which in turn led to the Lakota wars and Custer’s death two years later. A dozen or more dogs accompanied the expedition, but Cardigan again earned specific mention. Thirteen days into the expedition, Custer wrote Libbie:

“As I write, the dogs surround me; Cardigan is sleeping on the edge of my bed. Tuck at the head & Blucher nearby.”

Photographs taken during the expedition show some of the Custers’ dogs, but with a dozen or more hounds participating, we do not know if any of the images were Cardigan. Yet, the photographs still reflect Cardigan’s life with the expedition.

Armstrong Custer obviously thought highly of Cardigan, but Cardigan was Libbie Custer’s ‘best’ dog. This was in no small part due to his lifelong desire, despite his great size, to be her lapdog. Whenever possible, Cardigan would climb up on Libbie’s lap when she sat. Far too large to be a lapdog as an adult, Cardigan would place his head and chest on her lap and then pull his legs up on Libbie’s extended legs until he could balance his whole body.

He then “closed his eyes in a beatific state and sighed in content while I held him, until my foot went to sleep and I was cramped with his weight.”

The two had bonded in the aftermath of an earlier catastrophe. At some point, Cardigan had been separated from the other Custer dogs, so the pack no longer recognized him when he returned. The Custers made the mistake of placing Cardigan in the kennels without reintroducing him slowly. Consequently, the other male hounds attacked Cardigan in a terrible battle. Cardigan fought back but was outnumbered. He barely survived the fight and was grievously wounded. Libbie cared for Cardigan in the Custer home and during the months of his recuperation the two became very close.

After her husband’s death, Libbie and the other widows of the battle were forced to leave their military homes. Without her husband and his income, Libbie had no way to care for the many dogs they owned. As Duggan reports, Libbie reached out to a friend in Saint Paul, to aid her in finding homes for the dogs. Charles W. McIntyre was a government agent who managed two express companies and could arrange to ship the dogs to new owners. In Cardigan’s case, McIntyre did not have to send him far.

“I will anticipate a moment and speak of the final fate of Cardigan. When I left Fort Lincoln I asked some one to look out for his welfare, and send him, as soon as possible, to a clergyman who had been my husband's friend. My request was complied with, and afterwards, when the poor old dog died, his new master honored him by having his body set up by the taxidermist, and a place was given him in one of the public buildings in Minneapolis. I cannot help thinking that he was worthy of the tribute, not only because of the testimony thus given to the friendship of the people for his master, but because he was the bravest and most faithful of animals.”

- Elizabeth Bacon Custer, in ‘Boots and Saddles,’ pages 57-59.