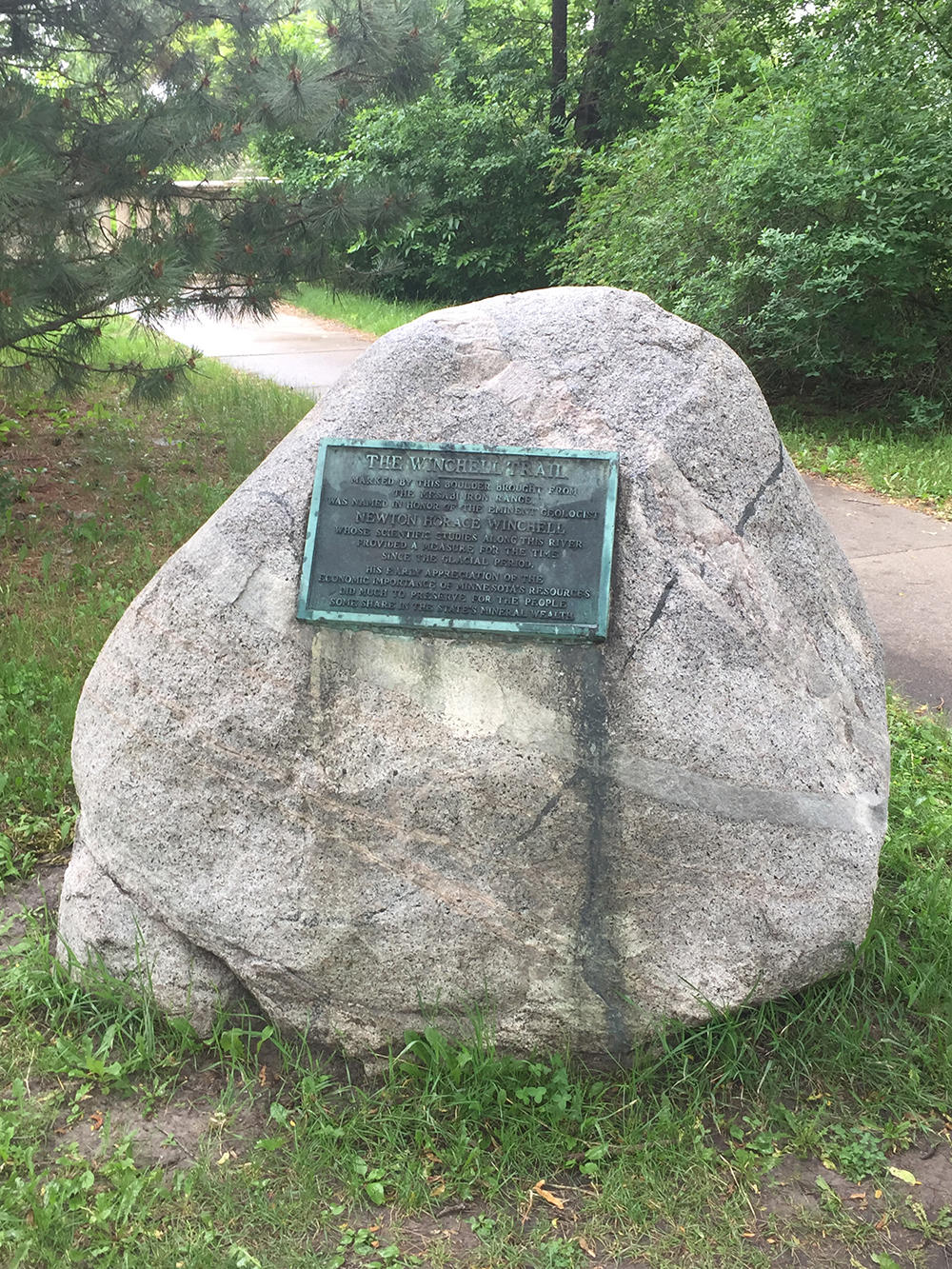

Many Twin Cities residents are familiar with the Winchell Memorial Boulder at the north entrance of the Winchell Trail, close to the southwest corner of the Franklin Avenue Bridge. The boulder was brought from the Mesabi Iron range of northern Minnesota by Newton Winchell’s oldest child Horace after his father’s death. For his family, the placing of the boulder was deeply personal, but most people attending its placement were acknowledging a legend, an eminent well-known geologist with a national reputation.

Memorial boulder by the Franklin Avenue Bridge that marks the northern entrance to the Winchell Trail.

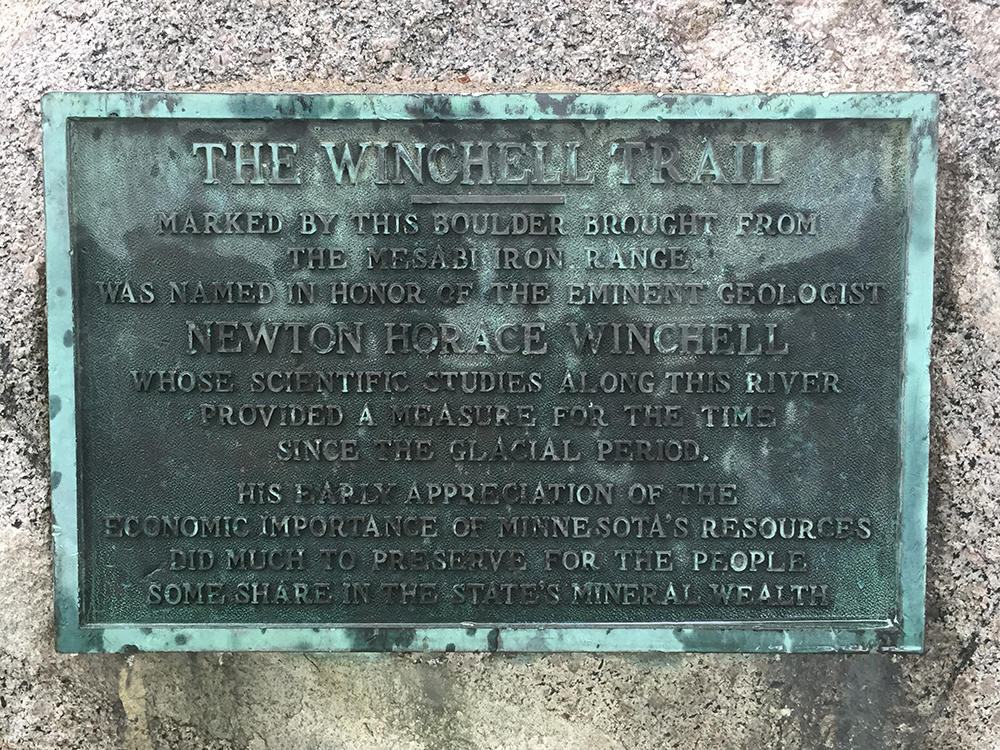

Plaque on memorial boulder at the north entrance of the Winchell Trail

However, another lesser-known Winchell boulder lies on the University of Minnesota’s east bank knoll. And rather than being brought in by workmen as part of a city’s celebration of a prominent scientist, it was dragged in by students to prank their teacher.

Winchell had a sense of humor appreciated by the students and sometimes recorded in the Home Hits and Happenings section of the Ariel, a monthly student publication that was an early forerunner of the present Minnesota Daily. In the December 19, 1877, issue, the Ariel reported an exchange between Winchell and a student.

Prof. of Mineralogy – “What is the difference between Hematite and Magnetite?”

Junior – “I think one contains no water.”

Prof. – “That’s right. Neither does the other.”

Another Winchell exchange made it into the February 11th Ariel issue that same year.

Junior in Blow Pipe Analysis – “Professor, have I got Apatite?”

Professor, absent mindedly – “I guess so. You generally have.”

Although some stories in the Home Hits and Happening section were factual others were apocryphal, so the veracity of these exchanges are uncertain. However, in both cases the Ariel writers cast Winchell in a favorable light, as someone with a sense of humor. In the February 11th Ariel they were also willing to tease Winchell when his struggles with mounting a large megatherium (giant ground sloth) cast led to the museum being closed that winter. Which suggests Winchell was a kindly instructor who was held in some affection by his students.

The Museum is still closed to visitors. That Megatherium is the most troublesome animal for a mere skeleton that we have never seen.

On an unseasonably warm January morning in 1878, Newton Winchell walked into his third-floor classroom in Old Main to find a large boulder, several hundred pounds in weight, perched on two chairs at the front of the room. Winchell’s students, inspired by his recent lecture on glaciers, had crafted a ‘glacial erratic’ for him, even filing grooves into the rock to make the boulder look like it was striated, or scratched, during glacial transport. Considering that they had to drag and carry the rock a considerable distance, this wasn’t an impromptu act but an elaborate arduous prank, suggesting considerable affection for its target. Winchell quickly and magnanimously played along, declaring the ‘erratic’ a magnificent specimen of its type. His response was most likely honed by raising five children of his own, and predicated on the swift recognition that without the students’ help the ‘erratic’ was likely to become a permanent fixture of his classroom.

Ironically, the winter of 1877-78 proved a poor setting for Winchell’s glacial lectures as it was the warmest winter of Minnesota’s historic record until the winter of 2023-24.[1] Most likely the result of an intense El Niño event, warm winter temperatures caused havoc across the state. In Minneapolis, temperatures from December through February averaged -1.67° C (29° F). However, as a result Winchell’s class created their glacial erratic in relative comfort.

The February 11th, 1878, issue of Ariel reported the boulder prank.

[1] https://www.dnr.state.mn.us/climate/journal/1877_1878_winter.html

The Professor of Geology expressed the wish that he had a specimen illustrating the glacial action. So the boys procured a bowlder about the size of Plymouth Rock, and having ruined all the engineer’s files in investing it with the unmistakable marks of the glacial epoch, deposited it on the floor in front of the Professor’s table. And now that he declared it an excellent specimen, they have serious thoughts of dropping it out the window.

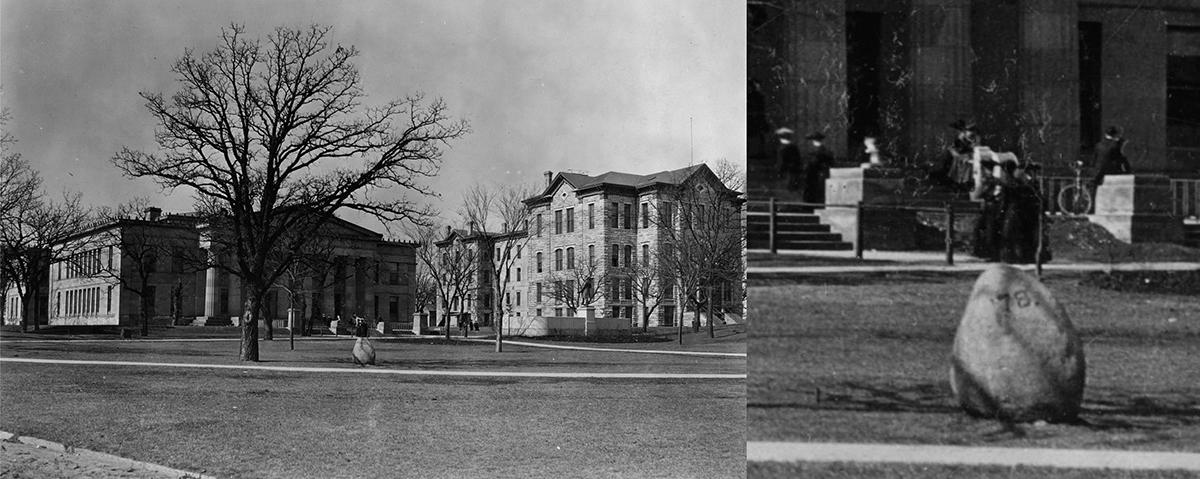

Word of the prank quickly spread and the boulder itself was adopted by that spring’s graduating class to be their memorial stone. Now graced by a deeply carved ’78, the stone was placed by an elm tree across from the university’s library in Burton Hall and close to the John Sargeant Pillsbury statue.

For at least three decades the stone stood untouched, an easily overlooked part of the campus landscape. I learned just how easily overlooked, when I came across a 1904 photograph of Burton Hall in the University Archives that shows the stone, clearly marked with an incised ’78, across the road from Burton Hall and just east of the Pillsbury statue. When my wife and I went to see if it was still there, we realized we had eaten lunch at a table less than eight feet from the stone yet had not noticed it.

1904 photograph of Burton Hall with 1878 Class Memorial Boulder in foreground and seen in closeup on right. Photograph courtesy of University of Minnesota Archives.

An hour spent scouring digitized photographs from the archives found other images of the stone, typically seen from a distance, but at least one image from 1908 chronicled its position relative to the road and Pillsbury’s statue.

1890 view of University of Minnesota campus. The 1878 Memorial Boulder can be seen on the far side of the fields. Photograph courtesy of University of Minnesota Archives.

1903 view of University of Minnesota campus with 1878 Memorial Boulder in distance and Winchell's Chair (a rock with two natural potholes) on the left next to Pillsbury Hall. Photograph courtesy of University of Minnesota Archives.

1905 photograph of University of Minnesota campus with 1878 Memorial Boulder. Note the ruins of Old Main in the background. Winchell's original classroom was destroyed by fire on Sept. 24, 1904. Photograph courtesy of University of Minnesota Archives.

1878 Memorial Boulder as seen from the north in 1908. Photograph courtesy of University of Minnesota Archives.

1878 Memorial Boulder (on right) viewed from Pleasant Drive in 1908. Photograph courtesy of University of Minnesota Archives.

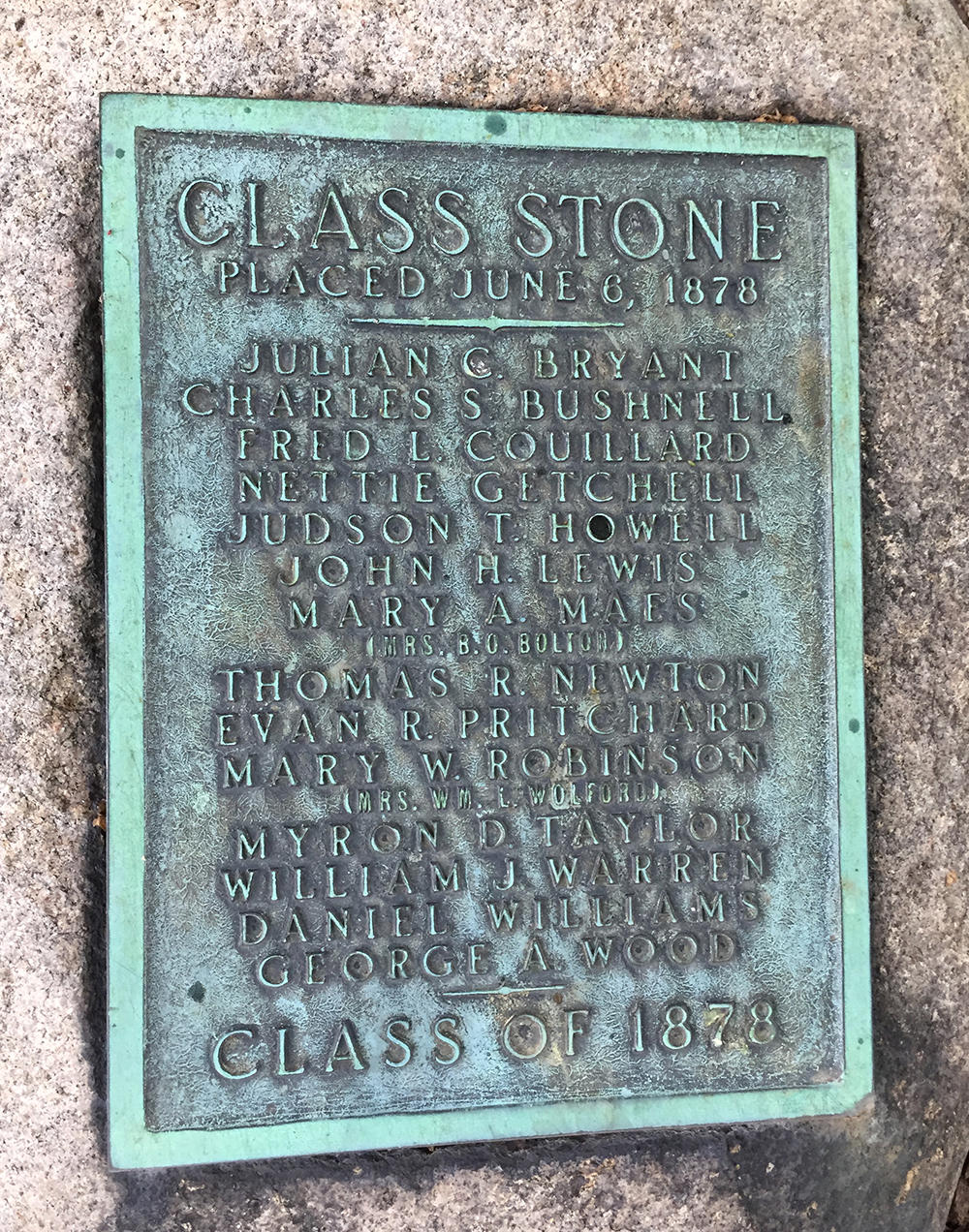

Through 1908, the boulder was in its original upright position. Sometime later it tilted, and a memorial tablet was added with the names of most of the 1878 graduating class. The tablet was not part of the original memorial as its orientation matches the stone’s current position and it also lists married names for two of the women graduates.

1878 Memorial Boulder with carved '78.

1878 Memorial boulder with plaque.

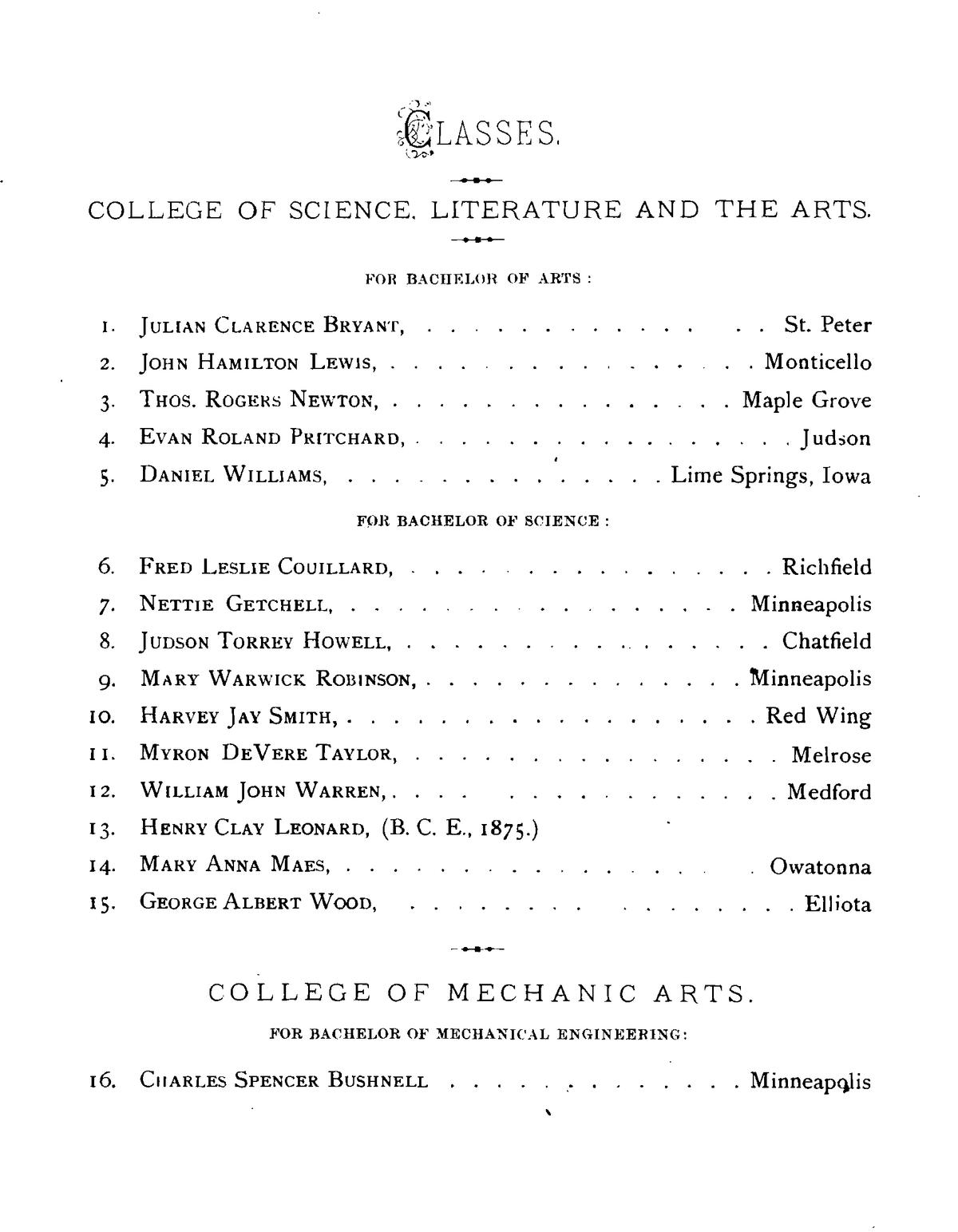

The 1878 graduating class consisted of three women and thirteen men but only the names of fourteen are listed on the boulder’s plaque. For some reason, Harvey Jay Smith of Red Wing and Henry Clay Leonard were not included.

Plaque on 1878 Class Memorial Boulder

1878 Class Commencement List. Courtesy of University of Minnesota Archives.

The 1878 class elected Mary Warwick Robinson to give the Salutatorian speech and Nettie Getchell to give the Valedictory speech. However, as the class was so small nearly everyone gave an oration during some part of the graduation ceremony. Julian Clarence Bryant chose to give a geology-themed analogy of their University of Minnesota experience in a short speech by the memorial stone and elm tree.

ADDRESS AT THE TREE by J. C. Bryant [1]

The boulder which was placed at the foot of the tree is one that was brought down from the far north during the last Glacial period. After calling attention to its rough journey, which left scars upon its surface and crushed its weaker companions, Mr. Bryant proceeded to draw a comparison between its history and that of the class:

We have, therefore, selected this granite boulder as a memorial stone of the class of ’78. Its early home was at the foot of the north pole. Six years ago we entered these classic halls with a strong force of resolute students. But the massive, ponderous faculty was in motion. The grinding was going on. Day after day, one after another, suffered his resolutions to become disintegrated and dropped out of the movement. But the process was too slow. Additional pressure was brought to bear. We resisted; and what could not be overthrown by powerful rams was insidiously besieged by strong drink. At this point “chemical and physical processes” manipulated by “experts” succeeded in reducing some of the impure granite. But the pure granite still resisted the most subtle “experiments.” At one time it was claimed that we had no sand. But that we have has been proved satisfactorily to all the grinders. And to-day the veterans of a six years conflict have gathered to rejoice over their afflications and to weep over their triumphs.

And as this granite not only shows the signs of a hard journey, but also of sterling worth, (for of this material the finest edifices and most collossal structures are erected, while the softer stones are ground into dust and blown about over the land), so this veteran class has the material to build structures that will rise to positions of influence and respect.

And as this, our memorial stone is to suggest the past, we look to yon noble elm for our inspiration for the future, and I take pleasure in introducing you to the class of ’78.

Although not nearly as well known as the boulder marking the Winchell Trail, I prefer this second Winchell boulder. As it reflects a comradery between Winchell and his students that gives a better indication of his character than the city’s later homage to a renowned scientist.

Ironically, for all the students’ effort and care to fake a convincing glacial erratic, Winchell had the last laugh that unseasonably warm January morning. As the students’ ‘fake erratic’ really was a true glacial erratic. Not one brought from the North Pole as Bryant imagined but one carried by non-vanished ice sheets from northern Minnesota.

Any comments, concerns, or suggestions?

email: Kent Kirkby ([email protected])

Sources:

The University of Minnesota Archives provided all historic photographs, the 1878 commencement list, as well as all Ariel content and images.

Color photographs of the Winchell boulders were taken by Kent C. Kirkby.

[1] Ariel – Volume 1, No. 9, June 7, 1878